Tag Archive for: UCLA Life Sciences

UCLA College Celebrates International Women’s Day

On International Women’s Day we give a shout-out to five…

Professor Seeks to Provide All Students with a Pathway to Research Success

When Tracy Johnson was an undergraduate working in a lab…

Esmeralda Villavicencio Is Working to Make Disease and Infertility a Thing of the Past

UCLA College division of Life Sciences student Esmeralda Isabel…

Michelle Craske to share how research can inform anxiety and depression treatment

For more than three decades, Michelle Craske has been trying…

First childhood flu helps explain why virus hits some people harder than others

Why are some people better able to fight off the flu than…

Hundreds of UCLA students publish paper analyzing 1,000 genes involved in organ development

A team of 245 UCLA undergraduates and 31 high school students…

UCLA psychology department receives $30 million from Anthony & Jeanne Pritzker Family Foundation

UCLA has received a $30 million commitment from the Anthony…

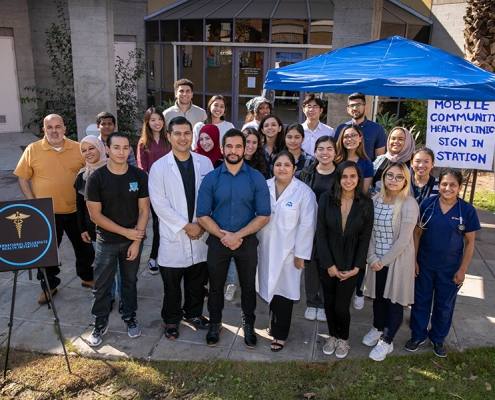

Student launches mobile health clinic to increase access to care

On a sunny autumn Saturday at the Southeast-Rio Vista YMCA…

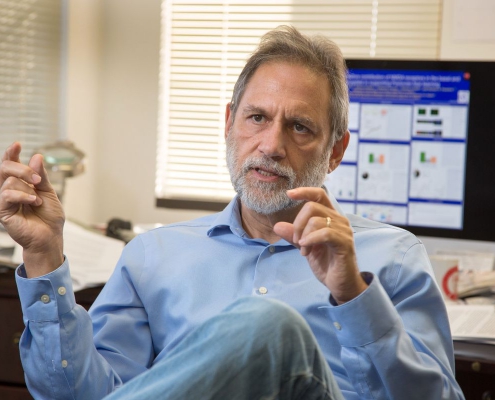

Chronic opioid treatment may raise risk of post-traumatic stress disorder, study finds

While opioids are often prescribed to treat people with trauma-related…

Meet UCLA Student Researcher Julia Nakamura

Meet fourth-year UCLA student researcher Julia Nakamura!

Julia…