Famartin/Wikimedia Commons

Famartin/Wikimedia CommonsMegadrought in southwestern North America is region’s driest in at least 1,200 years

Climate change is a significant factor, UCLA-led research…

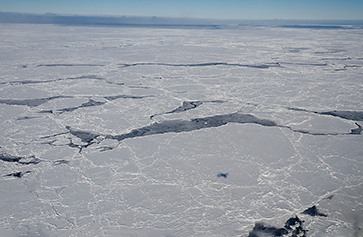

Michael Studinger/NASA

Michael Studinger/NASAAntarctic sea ice level could reach record low in 2022, UCLA climate scientist says

By David Colgan

Sometime in the next few weeks, during…

Courtesy of Paula White

Courtesy of Paula WhiteNotches on lions’ teeth reveal poaching in Zambia’s conservation areas

UCLA study shows the strange markings are the result of trapped…

Rendering by Perkins&Will, courtesy of Destination Crenshaw

Rendering by Perkins&Will, courtesy of Destination CrenshawDestination Crenshaw pays tribute to Black creativity and history in Los Angeles

UCLA faculty and alumni contributed ideas, expertise and artworks…

Yichao Zhao and Zhaoqing Wang/UCLA

Yichao Zhao and Zhaoqing Wang/UCLASweating the small stuff: Smartwatch developed at UCLA measures key stress hormone

Editor's note: This breakthrough by UCLA College researchers…

By Peter Hovarth

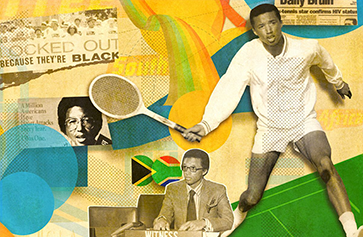

By Peter HovarthArthur Ashe: Champion for Justice

The tennis icon spent his life fighting for the oppressed.…

Credit: Khalid Ben-Srhir.

Credit: Khalid Ben-Srhir.Gift to UCLA’S Alan D. Leve Center for Jewish Studies bolsters field of Moroccan Jewish studies

By Margaret MacDonald

The UCLA Alan D. Leve Center for…

Courtesy of Rebecca Glasberg

Courtesy of Rebecca GlasbergSeeking the universal in the specific

Doctoral student Rebecca Glasberg blazes new trails in the study…

Photo credit: Courtesy of Ellen Sletten

Photo credit: Courtesy of Ellen SlettenProfessor’s invention is a kid-friendly introduction to the chemistry of light

Ellen Sletten’s Photonbooth gives L.A. students a picture-perfect…

Photo credit: Sean Brenner

Photo credit: Sean BrennerDays with hazardous levels of air pollutants are more common due to increase in wildfires

In Western U.S., health risks from ground-level ozone and fine…