Q&A: Space physicist Jacob Bortnik on the new UCLA SPACE Institute

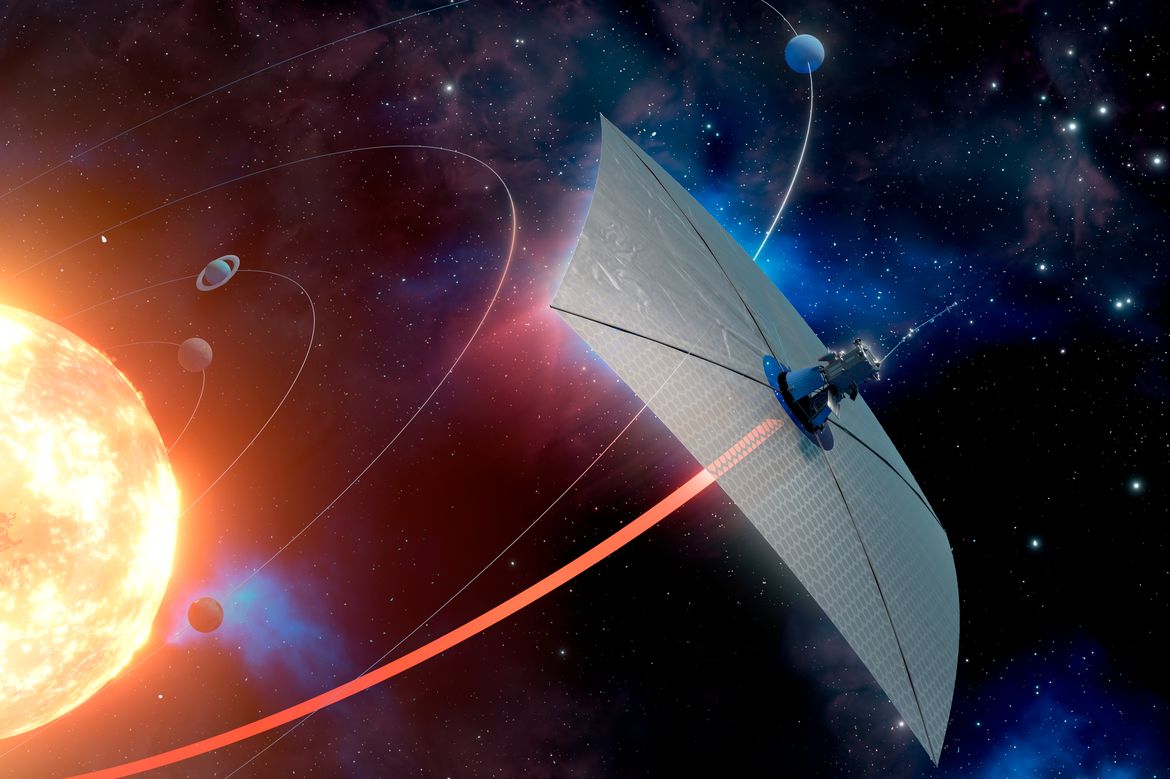

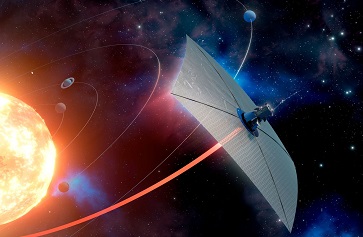

Illustration of a solar sail–propelled spacecraft leaving the solar system after a slingshot maneuver using the sun’s gravity to gain speed. The concept was developed by UCLA professor Artur Davoyan. Credit: Artur Davoyan and Ella Maru Studio

With the launch this spring of the UCLA SPACE Institute, the campus has a new umbrella organization to unite UCLA’s wide array of space-related research activities.

Courtesy of Jacob Bortnik

One of the institute’s leaders is Jacob Bortnik, a UCLA professor of space physics whose award-winning research helps predict space weather using artificial intelligence in order to protect people and technological systems, not only in orbit but also on the ground. In an interview, he spoke about why even non-scientists should be intrigued by the study of space and the new opportunities that the institute will create for UCLA scholars.

Why is the new institute so important?

I couldn’t even estimate how many faculty, researchers, technical staff, postdocs and students there are at UCLA whose work touches on space — it’s in the hundreds at least — but we don’t all know each other’s work yet. It’s important that we understand the kinds of problems other researchers are tackling, because very often, innovative approaches and solutions exist in different domains that can be brought into an adjacent discipline with tremendous success.

The institute will gather all of those amazing people, build relationships and move everything forward faster — think about something like the COVID-19 vaccine, where lab work that had been done in parallel for decades was ready to go when we needed it, and how much more progress we made after everyone was in conversation.

Aside from the obvious ones, which UCLA academic disciplines might have interesting links to space research?

It’s thrilling to think about how space research can overlap with other disciplines: space law, space-based biomedical technology, space medicine, sustainable agriculture beyond Earth, or even entertainment industry professionals working with the space environment as their creative medium. Those are just a few of the areas of research we hope to expand at UCLA.

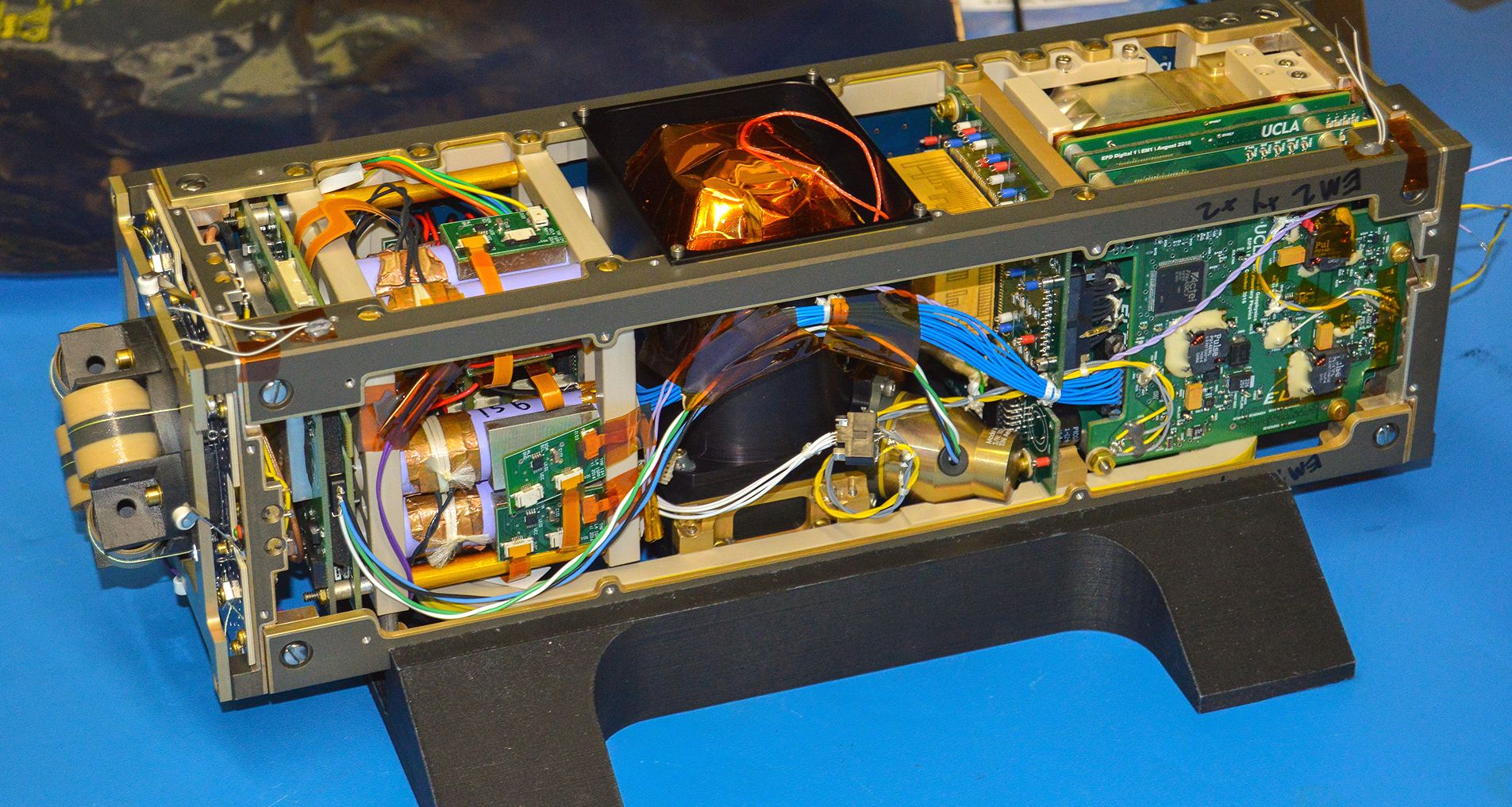

UCLA’s first student-built spacecraft, the ELFIN CubeSat, launched in 2018. It is still in orbit and gathering data. Image credit: Ethan Tsai

What new resources will the institute provide?

We are aiming to provide financial and administrative support for the development of innovative scientific experiments and satellite mission concepts, and the novel instruments needed to carry out those experiments.

Missions to Mars, Jupiter or Saturn cost billions of dollars, and gaining NASA approval for those experiments is very competitive — you have to prove there is zero chance of your experiment failing. Other labs and universities have internal development funds to cover the preliminary legwork it takes to demonstrate their projects’ readiness, but UCLA doesn’t.

Also, Southern California is the country’s aerospace hub, and it’s in the industry’s best interest to support UCLA, which is right in its backyard. The SPACE Institute will enable UCLA to spearhead big missions with NASA and give students a lot more opportunities to get involved in various aspects of mission and instrument design and scientific exploration from the ground up.

How else will the institute support students?

You don’t have to study astrophysics to work for NASA or become an astronaut; we want the SPACE Institute to show students how broad that scope of career paths really is. Ultimately, we would also like to offer internships to students from underrepresented groups. There is a huge need in the field for diversity, but it can be hard to climb the ladder with how much sacrifice and time is involved.

We plan to work with graduates in STEM fields who are interested in getting professional master’s degrees so they can enter the rapidly expanding space industry more quickly than by going through the typical pathway for doctoral students and postdocs. And we want to help current UCLA students connect with industry internships.

We will also begin public outreach programs, especially geared to K-12 students.

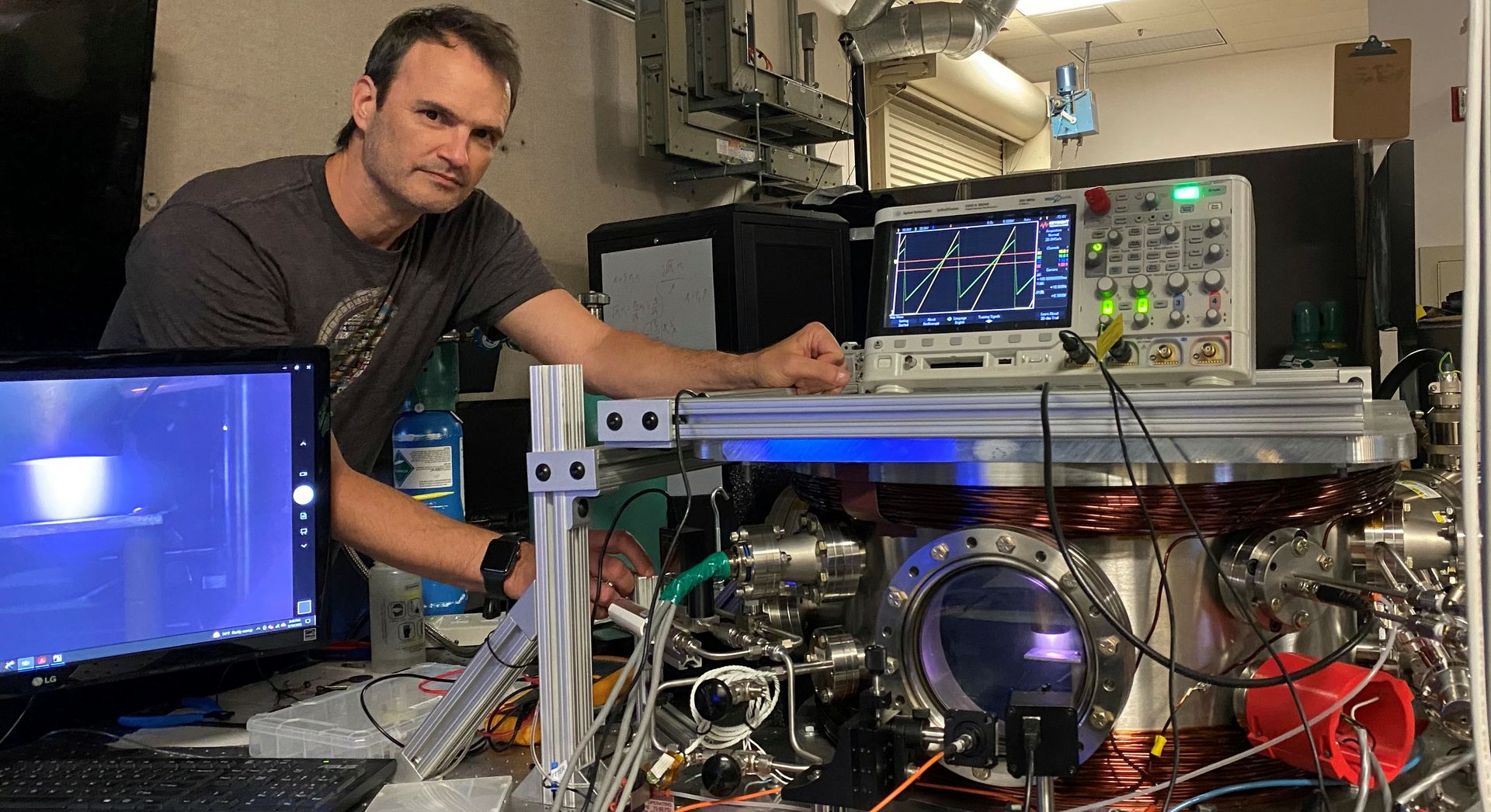

Professor Richard Wirz with a miniature xenon ion thruster, called MiXI, that was developed at the UCLA Samueli School of Engineering. The device can provide high-precision thrust for small satellite missions. Image credit: Wirz Research Group/UCLA

What current UCLA space-related projects do you find especially exciting?

UCLA students have built CubeSats — micro satellites that help scientists better understand magnetic storms in near-Earth space. UCLA researchers are discovering oceans and volcanoes on planetary moons. Space physicists are understanding the sun and plasma processes that lead to high-energy particles and the majestic aurorae. And UCLA astronomers are discovering exoplanets by the hundreds. It’s quite amazing!

Also, one of our engineering colleagues is working on a solar sail, a super-thin sheet that folds out to the size of an Olympic swimming pool and sends a spacecraft shooting out of the solar system about 300 times the speed of a high-powered rifle bullet. The technology could make vast interplanetary and interstellar distances more traversable.

Why should everyone, even non-scientists, be excited about space research?

It’s important to recognize that we’re on the cusp of something huge. We’re becoming a spacefaring civilization, much like when we became seafaring in the 15th century or aeronautical in the 20th century. People already are going up to the edge of space for tourism, and in the next decade or two, the number of manned spacecraft flights will increase, and we will likely send humans to the Moon — and possibly Mars.

Above all, I hope that elevating humanity’s aspirations will somehow elevate our consciousness, and make us less petty and more expansive and daring. It would do us all good to understand that we‘re all on this “spaceship Earth” together, and it is quite fragile.

This article originally appeared in the UCLA Newsroom. For more of Our Stories at the College, click here.

Credit: Artur Davoyan and Ella Maru Studio

Credit: Artur Davoyan and Ella Maru Studio Image by Elora Greenwale

Image by Elora Greenwale iStock.com/globalmoments

iStock.com/globalmoments