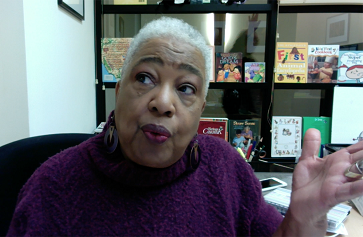

UCLA alumna seeks to preserve history of Black Boyle Heights

Shirlee Smith wants you to know about the Black community that used to live in the neighborhood: ‘We were there.’

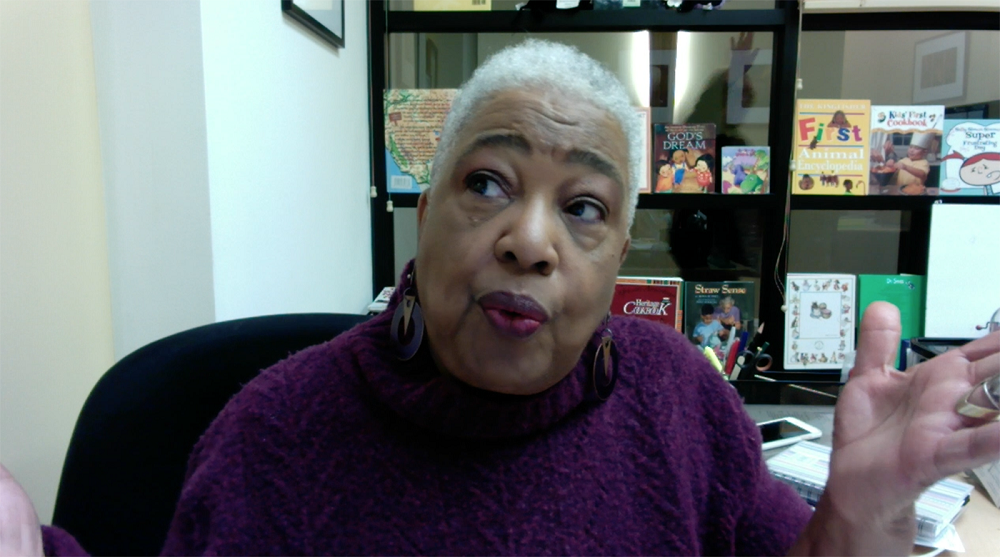

Shirlee Smith wrote a book about parenting titled “They’re Your Kids, Not Your Friends.” | Courtesy of Shirlee Smith

Nancy Gondo | November 7, 2022

Though Boyle Heights has a storied history as a multi-ethnic enclave of the 20th century, Shirlee Smith has noticed the Black community there often gets overlooked — something the UCLA alumna hopes to change.

“I’ve spent my adult years closing gaping mouths when asked where I’d grown up and my reply was Boyle Heights,” said Smith, 85. “People saw Boyle Heights as Jewish, as Latina, as Japanese. And so, the feedback has been, ‘Oh yes, the world needs to know: We were there.’”

The former Boyle Heights resident is working on a project to document and preserve the history of the Black people who used to live in the neighborhood. In some ways, Smith’s mother had started the legwork by collecting stories from families and entrusting them to one of her granddaughters.

“I read the 20 or so masterpieces and knew our stories had to be brought to light,” Smith said. She published some of the stories in Brooklyn and Boyle magazine, started the Black Boyle Heights Facebook group and in February, organized a virtual event with more than 50 people gathered online to share memories and honor their elders.

‘I’ll Take You There’

The event, called “I’ll Take You There,” honored four former residents who ranged in age from 93 to 101. Smith plans to turn the event into an annual celebration. She’s also collecting photos and stories, locating people, reviewing census data and getting in touch with local historians. Black Boyle Heights’ goals include publishing a directory of where the Black residents lived, setting up a podcast to tell their stories and creating a museum exhibit.

Boyle Heights drew a diverse mix of people in the early 20th century because the neighborhood east of the Los Angeles River was one of the few without restrictive racial covenants. Smith remembers hearing mariachi music up and down the block and walking past the Japanese Baptist church at the intersection of Evergreen and 2nd Street.

She didn’t think much about the diversity of Boyle Heights as a kid. But “as I grew up and interacted with a wide range of people, I discovered that fond memories were the opportunity to know up close people from so many cultures and be part of their traditions,” Smith said.

The close-knit Black community provided a built-in value system. Her next-door neighbor taught her how to knit and embroider; hairdresser Dolores Jones made house calls with straightening combs and curling irons in hand; Daddy Fred and Ma’ Bessie helped watch the neighborhood kids. But if anyone was caught acting out of line, word spread quickly.

“When you did wrong, it wasn’t just that Shirlee Pickett did wrong. It was the Pickett family,” Smith, née Pickett, said. “So when Dolores Jones came to your house to do your hair, you had to be polite. You may not have wanted to get your hair done, but you had to appreciate her.”

The neighborhood makeup started to change in the back half of the 1900s as racial covenants in Los Angeles lifted and families moved out of Boyle Heights. Today, few Black families remain in the now predominantly Latino neighborhood.

Meeting UCLA

Most minority students in Boyle Heights at the time weren’t being prepped for college, according to Smith. There were four paths, called “tracking” — academic, commercial, shop and home economics. Black and Latino girls were often tracked into home economics and commercial, where they would learn how to file papers. Few were put on the academic track.

“UCLA was not on my menu — there was no history,” Smith said. But in 1969, UCLA established the high potential program (now part of the Academic Advancement Program) to identify Black and Chicano students who might not meet the general entry criteria but are likely to succeed at the university. She applied and was accepted. “And that’s how I met UCLA,” she said.

The program started with a year of preparing students for university life. Smith wasn’t your typical college student fresh out of high school. She was a single mother of five children ranging in age from 7 months to 11 years.

“I was 30 years old when I hit the campus, and I had my youngest child in a stroller,” Smith said. “I took her to class with me, and that did not happen in 1968. There was no old lady on campus with a baby.”

As if that wasn’t tough enough, she got a C- on the first paper she wrote. She went to see the instructor, who told her she could redo the paper and gave her a copy of an A+ paper. That was a pivotal learning moment — Smith went on to graduate in 1973 with the distinction Department Scholar in Sociology.

Smith has since worked as a columnist for the Pasadena Star News, produced and hosted a cable TV show and written a book about parenting.

“Without UCLA, I doubt seriously that I would have had the courage to pursue any of my many accomplishments,” she said. “It’s really the reason I became a writer.”

If you’d like to contact Shirlee Smith regarding the Black Boyle Heights project:

info@blackboyleheights.org

aanbh1896@gmail.com

(626) 296-2777

This article originally appeared in the UCLA Newsroom. For more news and updates from the UCLA College, visit college.ucla.edu/news.