UCLA Professor Marissa López’s Summer Writers’ Workshop empowered young attendees to map out their unique vision of L.A.’s future history—and their role in it

What Gets Remembered

By Jonathan Riggs

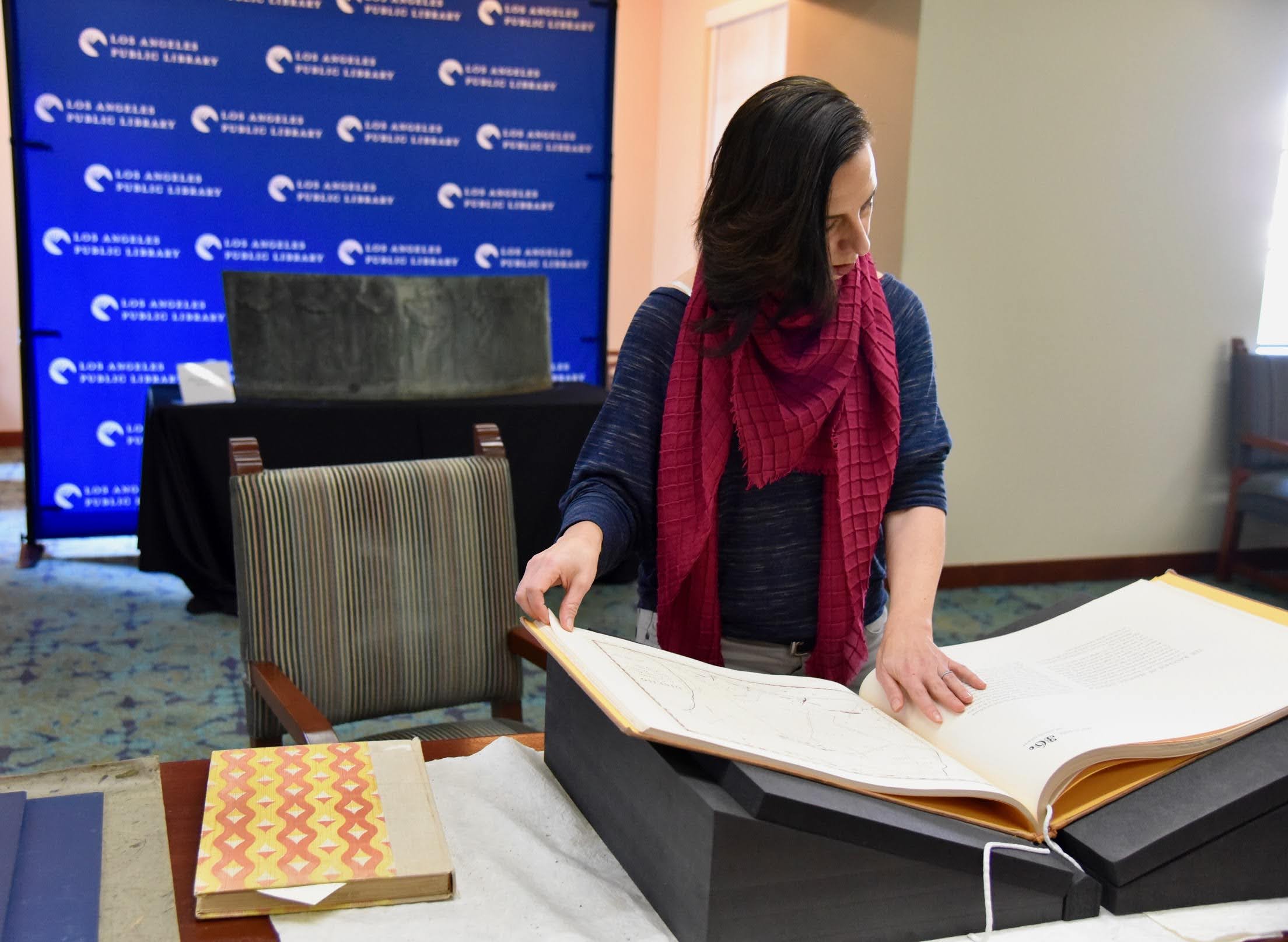

Professor Marissa López examines Robert Becker’s “Diseños of California Ranchos: Maps of thirty-seven Land Grants if 1822-1846 from the Records of the United States District Court, San Francisco” in the Rare Books room at Central Library downtown. PHOTO CREDIT: Yvonne Condes

There has never been one definitive Los Angeles. Spanning hundreds of years and countless cultures, the city represents something different for everyone. It belongs to us all, as young participants in the Summer Writers’ Workshop discovered in July.

An annual offering by creative writing nonprofit 826LA, the program featured something new this year: a collaboration between 826LA, UCLA and Professor of English and Chicana/o Studies Marissa López’s Picturing Mexican America project. The weeklong workshop brought middle and high school students together to examine—and imagine—both the future history of L.A. and their roles in that history, focusing on the questions, “Who makes decisions about what gets remembered?” and “How can we bring unseen or ignored things to light?”

López and her graduate students Efren Lopez (no relation), Robert Mendoza and Gabriela Valenzuela, as well as their partners at 826LA, including program coordinator Cecilia Gamiño, created the workshop to empower young writers to think about their city in new ways and about themselves as active participants in history.

“Working together on this project underscored how the process of rewriting a history of Los Angeles must be a collaborative project rather than an individual endeavor,” Mendoza says. “We made sure to let our students know that we were excited to be coworkers with them in the production of a new type of history.”

The program began with López sharing research from her Picturing Mexican America project. Actor and writer Xavi Moreno then came in to help the students develop an “I am…” poem that described their Los Angeles—and themselves.

Examples of collaborative maps the students drew using Zoom’s whiteboard feature.

“Hearing Xavi read his poem about the sights, smells and sounds of growing up in Boyle Heights literally gave me goosebumps,” López says. “At the end of the week, we recorded the students reading their poems. Their writing was … moving, sharing such personal fears, hopes and joys. It was a remarkable experience.”

The workshop also included a session titled “Imagining Space,” led by Valenzuela, in which students plumbed the California State Archives’ Diseño Collection, a free digital resource of 493 hand-drawn maps (diseños) of nineteenth-century land grants, to compare them with surveyors’ maps of the same places after the Mexican-American War.

“I was born and raised in Los Angeles, and it was important to me to remind 826LA students, many of whom are students of color, that they have as much a right as anyone else to learn firsthand about the city in which they live,” Valenzuela says. “I hope that working with the diseños showed them that L.A. has always been a place held up by people of color, despite what systematic erasure tells us.”

She then asked students to think about what being from Los Angeles meant to them, and what places and resources they would want to archive as they drew their own maps of the city. The resulting diseños showcased local grocery stores, favorite landmarks, beloved homes and even major freeways, painting unique portraits of life in 21st-century Los Angeles.

“It was interesting to see what was important to them and how that translates to scale, which helped them understand cartographic features of the diseños in ways that connect them on a personal level,” says López. “After all, the diseños were made by real people who lived, laughed and loved on this land that first was taken from the Tongva, then was taken from Mexican families, and now is home to things like the Glendale Galleria. Engaging with space in this deeply personal way helped the students understand land as a narrative object and to see themselves as people with world-making story power.”

After thoughtfully examining the past and the present, participants next looked to the future, exploring how artists across multiple mediums have envisioned the L.A. of tomorrow. Then, guided by Efren Lopez, students created their own vision of the future of their city, while also writing about themselves and their lives from the perspective of historians working centuries ahead.

“This project taught me that the type of historical research I do—and the public humanities overall—are translatable to other communities outside of academia and to all ages,” Lopez says. “More than ever, it is important that we give students space to think critically and historically about the world they are in, and the world they will build.”

As impactful as the workshop was for the attendees, it proved even more so for Marissa López and her graduate students.

“First and foremost, Efren, Robert and Gabriela are brilliant scholars and excellent teachers with deep roots in and powerful commitments to the city and people of Los Angeles,” she says. “As the director of Efren’s and Gabriela’s dissertations and a member of Robert’s committee, I saw the workshop experience as an occasion for career development: they were able to build out the public engagement aspects of their dossiers, broaden their professional networks and gain valuable perspective on their future career trajectories.”

Much like the students they taught, López’s graduate students came away with a renewed vision for their unique roles in shaping the future, including helping to dispel the myth that a humanities higher education only equips students to teach.

“There is a wide world of work out there and a large market for their skills. After all, our field at its core is discovering, communicating, building community and imagining new worlds into being,” López adds. “That is what scholarly research and writing is all about; it is also what organizations like 826LA do. The advanced training of a humanities Ph.D. can produce problem-solving visionaries uniquely equipped to make the world a better place in ways that we can’t even begin to imagine.”

Participant Rami Gross remixed archival photos to tell his own, speculative history using an image of Margarita Reyes, daughter of Jose Isidro Reyes and Maria Antonio Villa de Reyes who owned a large tract of land in Orange County during the 19th century (from UC Irvine Library, ca 1875) engaged in a lightsaber duel on the Death Star with “A youngster wearing traditional Chinese clothing” standing next to a Chinese banner in Chinatown (from LA Public Library, ca 1900). “One of the things we asked the students to think about is what kinds of images we have in the archives and how they’re described,” says Professor Marissa López. “Why do we know Margarita’s name but the youngster is just a ‘youngster’? What does it mean to see and be seen, to be named or unnamed in the historical record?”

COLLAGE CREDIT: Rami Gross

Martin Seifert

Martin Seifert