Ancient fossil microorganisms indicate that life in the universe is common

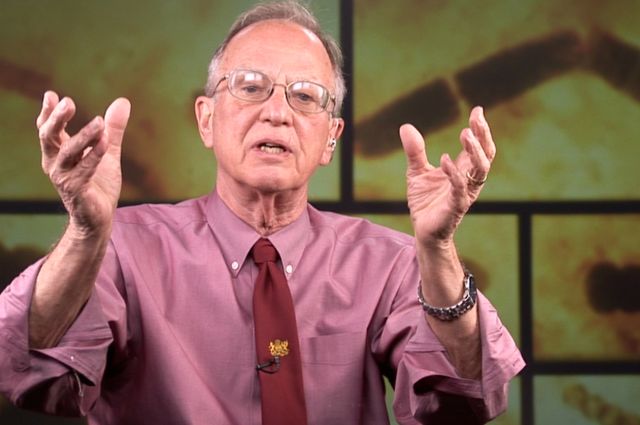

J. William Schopf and colleagues from UCLA and the University of Wisconsin analyzed the microorganisms with cutting-edge technology called secondary ion mass spectroscopy.

Anew analysis of the oldest known fossil microorganisms provides strong evidence to support an increasingly widespread understanding that life in the universe is common.

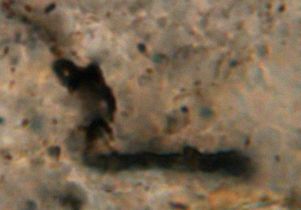

The microorganisms, from Western Australia, are 3.465 billion years old. Scientists from UCLA and the University of Wisconsin–Madison report today in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences that two of the species they studied appear to have performed a primitive form of photosynthesis, another apparently produced methane gas, and two others appear to have consumed methane and used it to build their cell walls.

The evidence that a diverse group of organisms had already evolved extremely early in the Earth’s history — combined with scientists’ knowledge of the vast number of stars in the universe and the growing understanding that planets orbit so many of them — strengthens the case for life existing elsewhere in the universe because it would be extremely unlikely that life formed quickly on Earth but did not arise anywhere else.

“By 3.465 billion years ago, life was already diverse on Earth; that’s clear — primitive photosynthesizers, methane producers, methane users,” said J. William Schopf, a professor of paleobiology in the UCLA College, and the study’s lead author. “These are the first data that show the very diverse organisms at that time in Earth’s history, and our previous research has shown that there were sulfur users 3.4 billion years ago as well.

A microorganism analyzed by the researchers

“This tells us life had to have begun substantially earlier and it confirms that it was not difficult for primitive life to form and to evolve into more advanced microorganisms.”

Schopf said scientists still do not know how much earlier life might have begun.

“But, if the conditions are right, it looks like life in the universe should be widespread,” he said.

The study is the most detailed ever conducted on microorganisms preserved in such ancient fossils. Researchers led by Schopf first described the fossils in the journal Science in 1993, and then substantiated their biological origin in the journal Nature in 2002. But the new study is the first to establish what kind of biological microbial organisms they are, and how advanced or primitive they are.

For the new research, Schopf and his colleagues analyzed the microorganisms with cutting-edge technology called secondary ion mass spectroscopy, or SIMS, which reveals the ratio of carbon-12 to carbon-13 isotopes — information scientists can use to determine how the microorganisms lived. (Photosynthetic bacteria have different carbon signatures from methane producers and consumers, for example.) In 2000, Schopf became the first scientist to use SIMS to analyze microscopic fossils preserved in rocks; he said the technology will likely be used to study samples brought back from Mars for signs of life.

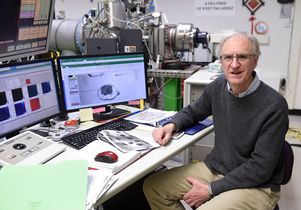

The Wisconsin researchers, led by geoscience professor John Valley, used a secondary ion mass spectrometer — one of just a few in the world — to separate the carbon from each fossil into its constituent isotopes and determine their ratios.

University of Wisconsin professor John Valley

“The differences in carbon isotope ratios correlate with their shapes,” Valley said. “Their C-13-to-C-12 ratios are characteristic of biology and metabolic function.”

The fossils were formed at a time when there was very little oxygen in the atmosphere, Schopf said. He thinks that advanced photosynthesis had not yet evolved, and that oxygen first appeared on Earth approximately half a billion years later before its concentration in our atmosphere increased rapidly starting about 2 billion years ago.

Oxygen would have been poisonous to these microorganisms, and would have killed them, he said.

Primitive photosynthesizers are fairly rare on Earth today because they exist only in places where there is light but no oxygen — normally there is abundant oxygen anywhere there is light. And the existence of the rocks the scientists analyzed is also rather remarkable: The average lifetime of a rock exposed on the surface of the Earth is about 200 million years, Schopf said, adding that when he began his career, there was no fossil evidence of life dating back farther than 500 million years ago.

“The rocks we studied are about as far back as rocks go.”

While the study strongly suggests the presence of primitive life forms throughout the universe, Schopf said the presence of more advanced life is very possible but less certain.

One of the paper’s co-authors is Anatoliy Kudryavtsev, a senior scientist at UCLA’s Center for the Study of Evolution and the Origin of Life, of which Schopf is director. The research was funded by the NASA Astrobiology Institute.

In May 2017, a paper in PNAS by Schopf, UCLA graduate student Amanda Garcia and colleagues in Japan showed the Earth’s near-surface ocean temperature has dramatically decreased over the past 3.5 billion years. The work was based on their analysis of a type of ancient enzyme present in virtually all organisms.

In, 2015 Schopf was part of an international team of scientists that described in PNAS their discovery of the greatest absence of evolution ever reported — a type of deep-sea microorganism that appears not to have evolved over more than 2 billion years.