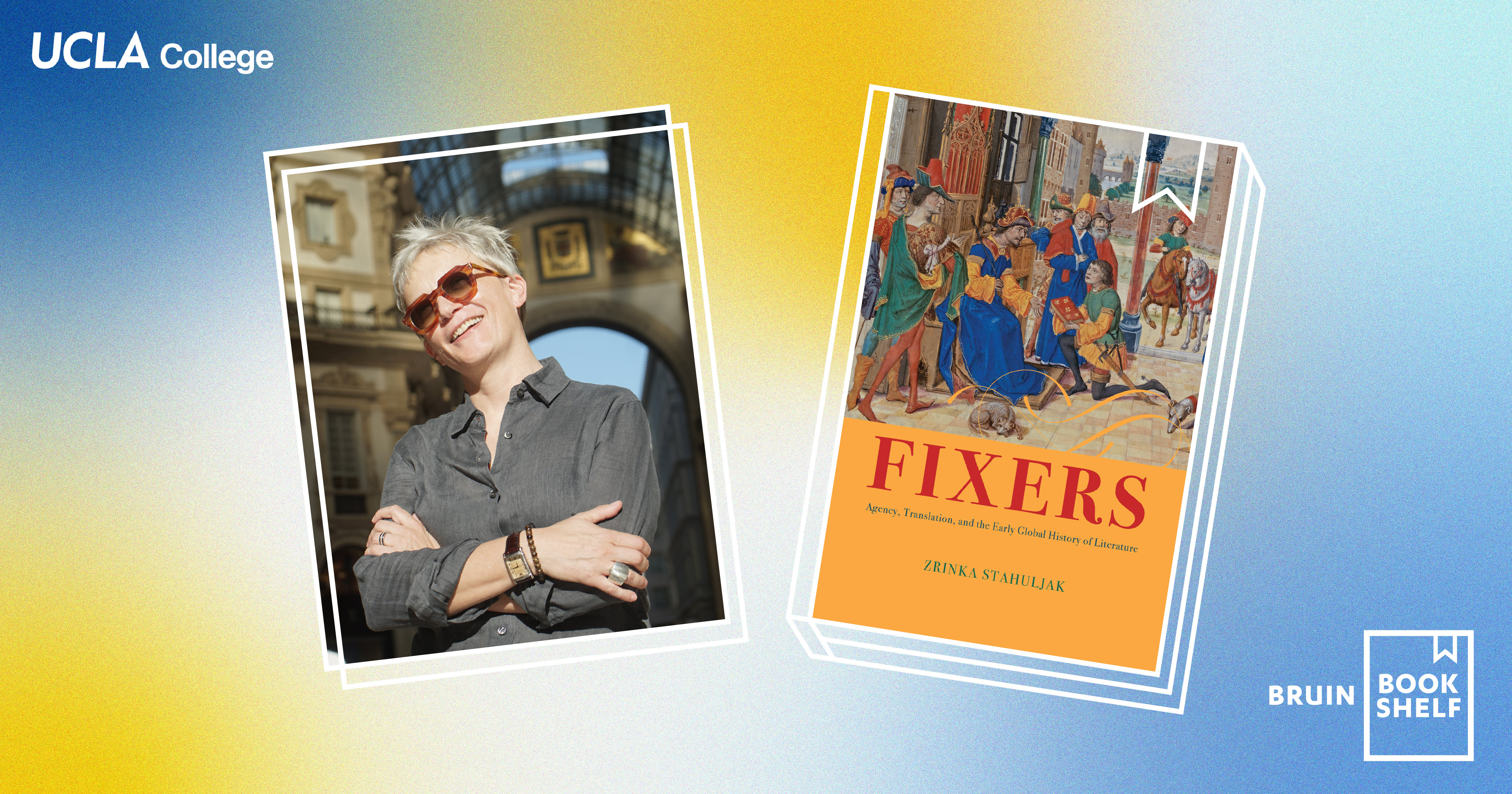

Bruin Bookshelf Spotlight: Professor Zrinka Stahuljak

‘Fixers: Agency, Translation, and the Early Global History of Literature’ by Zrinka Stahuljak, UCLA professor of comparative literature and European languages and transcultural studies

By Alvaro Castillo | April 30, 2024

In the latest installment of our Q&A series, Bruin Bookshelf Spotlight, we spoke with Zrinka Stahuljak, author of “Fixers: Agency, Translation, and the Early Global History of Literature.” In her book, Stahuljak challenges scholars in medieval and translation studies to reimagine the role of translators and interpreters in the medieval era and to rethink how their involvement impacted the circulation of ideas and texts in the medieval world.

A professor of comparative literature as well as European languages and transcultural studies, Stahuljak is the director of the CMRS Center for Early Global Studies and co-director of the UCLA Program in Experimental Critical Theory. In this work, she presents a new history of global literature by treating translators as active agents mediating cultures.

“The book is in a critical conversation with several important fields and disciplines: history, art history, literary criticism and history, translation and interpreting studies,” she says. “But, as one of the book reviewers observed, there is no such book on the market, in either scope or breadth.”

As a result, Stahuljak’s book not only reimagines the impact interpreters had in the medieval era, it also presents an innovative and interdisciplinary approach to reimagining a new history of literature, art, translation and social exchange.

What inspired you to write this book?

This book is the first time I confronted my own history of being a fixer during the wars in the former Yugoslavia (1991–99). I was taught to think of my role as a wartime interpreter, only to recognize myself — as the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan progressed — in the figure of the fixer. Fixers are much more than linguistic interpreters and that is the core message of the book, which tests history, art history and literary history against translation and interpreting studies. They are agents who act as interpreters, local informants, guides, brokers, personal assistants and more.

Bilingual communication is a history of these multifunctional intermediaries who enable, facilitate and mediate through spaces of unintelligibility and, as a consequence, enable communication and exchange. But they are not neutral, silent or faithful; rather, they embody a ternary position. Fixers break up our modern binary and dialectical modes of analyses and ways of knowing. In that sense, the book is paradigm-shifting for many of our Western-based epistemologies that are anchored in the dialectical oppositions and dualisms (e.g. body-mind; active-passive; male-female; nature-culture, etc.). The book is also about circulation, reciprocity, gift-exchange and commensuration that go beyond the standard anthropological study of gift and debt.

Can you discuss the publication journey of this book?

“Fixers” embodies its own topic of circulation, transmission and exchange. Although the project immediately won the support of the Fulbright in 2013, it would never have been the same without the invitation of Elizabeth Morrison, senior curator of manuscripts at the J. Paul Getty Museum, to work on medieval Burgundy and its cultural and artistic production during 2014 and 2015. And then I won a Guggenheim Fellowship in 2016! The most amusing fact, for me, is that this book project that began in 2012 literally spawned two other books, published in 2020 and 2021 respectively, all in the aftermath of the co-authored Getty book.

“Les Fixeurs au Moyen Âge” (Medieval Fixers; Seuil 2021) was an offshoot of the larger project that focused on the comparison of the medieval Near East and contemporary Afghanistan and the ethical and political issues fixers raise in Western interventions around the world, whether military or humanitarian. “Médiéval contemporain. Pour une littérature connectée” (Medieval Contemporary: For a Connected Literature; Macula 2020) is a theory of the practice of fixers that provides a new methodology for the study of the European Middle Ages and humanistic inquiry.

And “Fixers” did for me what fixers do: it enabled, facilitated and mediated extensive knowledge and writing, and has taken me around the world, from visiting professorships at the Collège de France (2018), the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales (2023), Université-Rennes 2 (2016), Iceland (2022) and Taiwan (2022), to becoming a corresponding member of the Croatian Academy of Arts and Sciences (2020).

What does the UCLA College mean to you and your work?

I believe in the mission of a public university and in public humanities, which inspired public-facing collaborations with the J. Paul Getty Museum and a TV show on the Holy Grail that aired on the French-German channel ARTE, in addition to many radio and online appearances, and in festivals and bookstores in Europe. In that sense, I feel that I am a fixer between the public and the university as an institution. Of course, teaching is the primordial fixer function!

What are you working on next?

I am deeply engaged in our public mission of a land-grant and community-engaged institution. In July 2023, Shannon Speed, the director of UCLA’s American Indian Studies Center, and I received a $1 million grant from the Mellon Foundation for our “Race in the Global Past through Native Lenses” project.

The three-year grant supports scholars-in-residence, faculty and students, community advisors, postdoctoral fellows, and tribal managers who compare and co-learn the historical articulations of “race” in different parts of the globe in the period broadly defined as “premodern” or “pre-/early colonial.” We are now eight months into the project and believe that we can go beyond community-engaged to community-created scholarship.

The project specifically focuses on racialization, the creation of difference in the moment of precolonial or early colonial expansion, with the intent to effect change in Western epistemologies and the Western university. This is important for two reasons. On the one hand, we want to understand how lives, knowledges, worldviews, land and water, objects, practices and relations have been racialized by Western epistemology in that early contact period, which then proceeded to exclude them from the Western construction of the world. In parallel to tracing the making (the genealogy) of the Western categories of “indigeneity,” we also aim to understand how the lives, knowledges, worldviews, land and water, objects, practices and relations were understood by Native communities in their contexts and in their time. We then wish to bring these philosophies and worldviews — and their history — into the university and academic disciplines, not with the goal to assimilate it to the Western way of telling history and transmitting knowledge, but rather with the goal of reshaping Western disciplinary frames.

As a result, I am currently writing two more books: one on the general notion of intermediary that takes us out of the binary dialectic and quandary into a ternary positionality and space. The second one expands on my earlier work on the relationship of the medieval and contemporary, exploring the circulations between the (inadequately named) pre-colonial and decolonial moments. The idea is to transcend the temporal and cultural division of the colonial and, again, move the grounds on which Western disciplinarity rests.

Is there anything else you would like to say?

I hope this book will find an eager audience with its new methodology of reading and writing history and literary history, as well as the history of translation. I also hope that students at UCLA will engage with the methodology, which will be on view in the next graduate seminar on “Ternary Positionality: Relationality, Decoloniality and Interpretation” that I am teaching this spring for the UCLA Experimental Critical Theory Program.

Follow the CMRS Center for Early Global Studies on Instagram and Facebook.

If you are a member of the UCLA College community who has published a book, tell us about it.