UCLA researchers discover source of super-fast ‘electron rain’

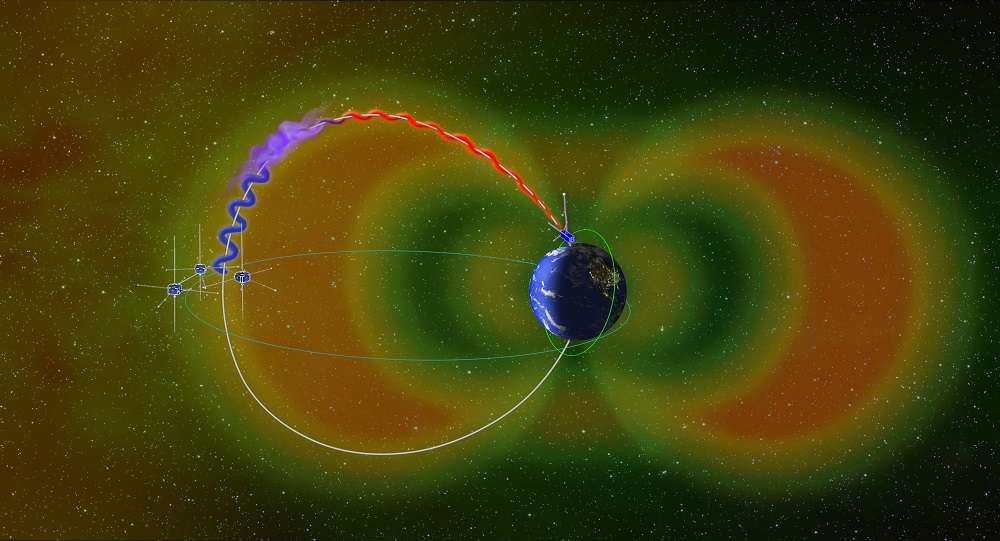

Electrons in a Van Allen radiation belt (blue) encounter whistler waves (purple) and are sent raining toward the north pole (red). THEMIS satellites are seen near the radiation belt, while UCLA’s ELFIN hovers above Earth. Image source: Zhang, et al., Nature Communications, 2022

UCLA scientists have discovered a new source of super-fast, energetic electrons raining down on Earth, a phenomenon that contributes to the colorful aurora borealis but also poses hazards to satellites, spacecraft and astronauts.

The researchers observed unexpected, rapid “electron precipitation” from low-Earth orbit using the ELFIN mission, a pair of tiny satellites built and operated on the UCLA campus by undergraduate and graduate students guided by a small team of staff mentors.

By combining the ELFIN data with more distant observations from NASA’s THEMIS spacecraft, the scientists determined that the sudden downpour was caused by whistler waves, a type of electromagnetic wave that ripples through plasma in space and affects electrons in the Earth’s magnetosphere, causing them to “spill over” into the atmosphere.

Their findings, published March 25 in the journal Nature Communications, demonstrate that whistler waves are responsible for far more electron rain than current theories and space weather models predict.

“ELFIN is the first satellite to measure these super-fast electrons,” said Xiaojia Zhang, lead author and a researcher in UCLA’s department of Earth, planetary and space sciences. “The mission is yielding new insights due to its unique vantage point in the chain of events that produces them.”

Central to that chain of events is the near-Earth space environment, which is filled with charged particles orbiting in giant rings around the planet, called Van Allen radiation belts. Electrons in these belts travel in Slinky-like spirals that literally bounce between the Earth’s north and south poles. Under certain conditions, whistler waves are generated within the radiation belts, energizing and speeding up the electrons. This effectively stretches out the electrons’ travel path so much that they fall out of the belts and precipitate into the atmosphere, creating the electron rain.

► Curious about how whistler waves got their name? Have a listen.

One can imagine the Van Allen belts as a large reservoir filled with water — or, in this case, electrons, said Vassilis Angelopoulos, a UCLA professor of space physics and ELFIN’s principal investigator. As the reservoir fills, water periodically spirals down into a relief drain to keep the basin from overflowing. But when large waves occur in the reservoir, the sloshing water spills over the edge, faster and in greater volume than the relief drainage. ELFIN, which is downstream of both flows, is able to properly measure the contributions from each.

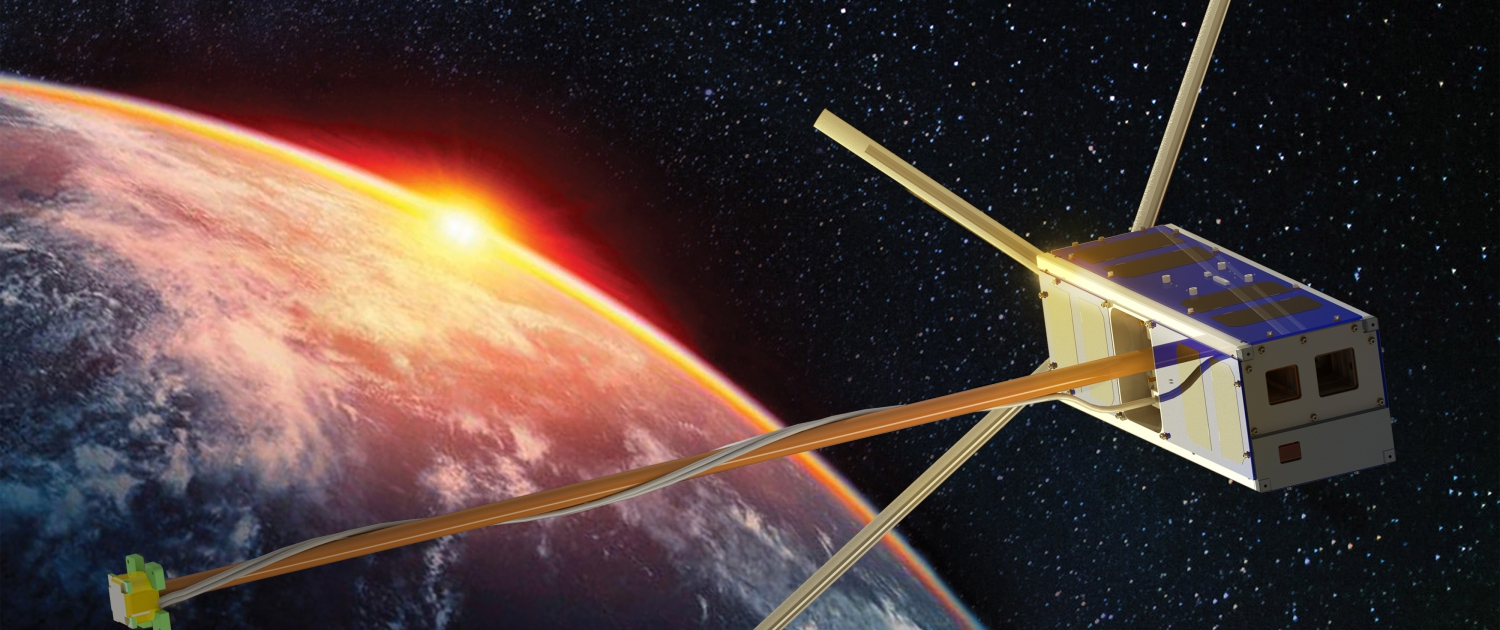

An artist’s rendering of one of UCLA’s bread loaf–sized ELFIN satellites in low-Earth orbit. Image credit: Emmanuel Masongsong/UCLA

The low-altitude electron rain measurements by ELFIN, combined with the THEMIS observations of whistler waves in space and sophisticated computer modeling, allowed the team to understand in detail the process by which the waves cause rapid torrents of electrons to flow into the atmosphere.

The findings are particularly important because current theories and space weather models, while accounting for other sources of electrons entering the atmosphere, do not predict this extra whistler wave–induced electron flow, which can affect Earth’s atmospheric chemistry, pose risks to spacecraft and damage low-orbiting satellites.

The researchers further showed that this type of radiation-belt electron loss to the atmosphere can increase significantly during geomagnetic storms, disturbances caused by enhanced solar activity that can affect near-Earth space and Earth’s magnetic environment.

“Although space is commonly thought to be separate from our upper atmosphere, the two are inextricably linked,” Angelopoulos said. “Understanding how they’re linked can benefit satellites and astronauts passing through the region, which are increasingly important for commerce, telecommunications and space tourism.”

Since its inception in 2013, more than 300 UCLA students have worked on ELFIN (Electron Losses and Fields investigation), which is funded by NASA and the National Science Foundation. The two microsatellites, each about the size of a loaf of bread and weighing roughly 8 pounds, were launched into orbit in 2018, and since then have been observing the activity of energetic electrons and helping scientists to better understand the effect of magnetic storms in near-Earth space. The satellites are operated from the UCLA Mission Operations Center on campus.

“It’s so rewarding to have increased our knowledge of space science using data from the hardware we built ourselves,” said Colin Wilkins, a co-author of the current research who is the instrument lead on ELFIN and a space physics doctoral student in the department of Earth, planetary and space sciences.

Members of the current ELFIN UCLA student team responsible for the daily satellite operations at the mission operations center, which is housed in the Geology Building on campus. Image credit: Ethan Tsai/UCLA

Read more about UCLA’s ELFIN Mission on Newsroom:

► We have liftoff: UCLA’s student-built ELFIN satellites

► UCLA students launch project that’s out of this world

► Undergrads are first to build an entire satellite on campus

This article originally appeared in the UCLA Newsroom. For more news and updates from the UCLA College, visit college.ucla.edu/news.

Image source: Zhang, et al., Nature Communications, 2022

Image source: Zhang, et al., Nature Communications, 2022 Image credit: Alyssa Bierce/UCLA College

Image credit: Alyssa Bierce/UCLA College Image credit: Don Liebig/ASUCLA

Image credit: Don Liebig/ASUCLA