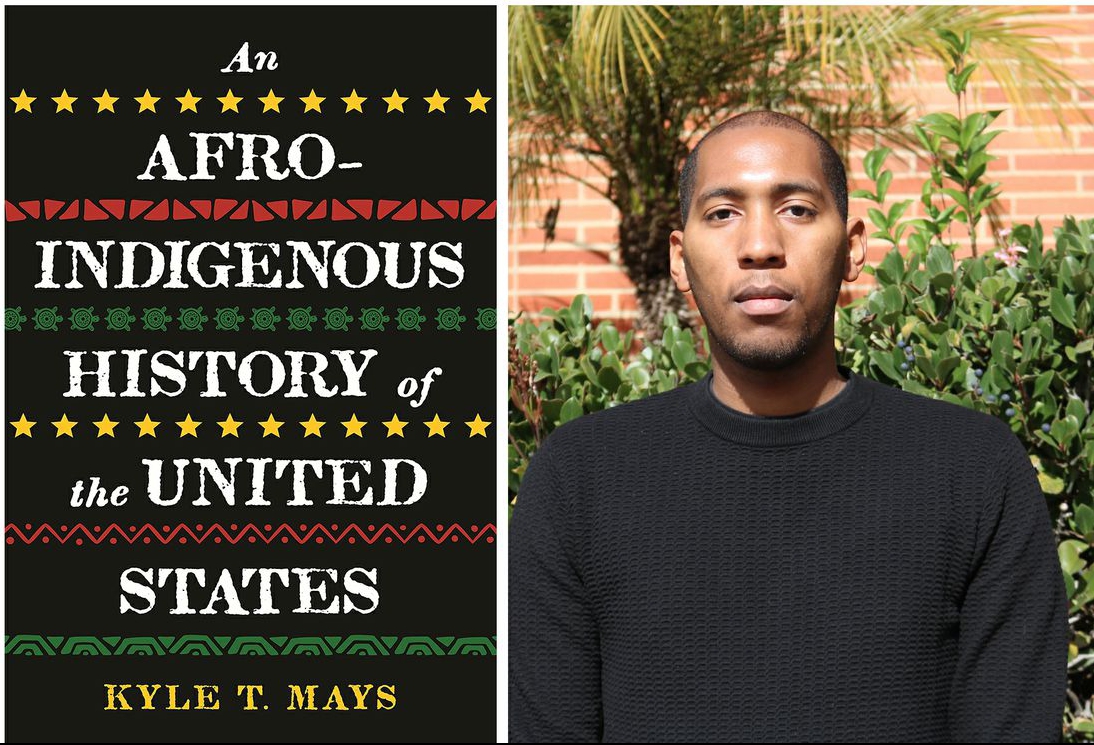

Professor Kyle T. Mays spotlights Black–Indigenous solidarity in new book

By Jessica Wolf

In ‘An Afro-Indigenous History of the United States,’ Kyle Mays reframes U.S. history

Mays’ narrative is infused throughout with his personal experiences as an Afro-Indigenous scholar. “As a Black and Indigenous person, I suppose I’m just Mr. In-between, a brotha without a home,” he writes. Photo credit: UCLA

With his book “An Afro-Indigenous History of the United States,” assistant professor Kyle Mays traverses broad, complex and intimate territory.

Mays, who is Black and Saginaw Anishinaabe, teaches African American studies and American Indian studies at UCLA. His latest book is billed as the first to examine the intersecting struggles of Black and Native Americans. In it, he delves into the the country’s founding; early 20th-century global reckonings with racism, like the multinational Universal Races Congress in 1911; the Black Power and Red Power movements of the 1960s and 1970s; and Black and Indigenous pop culture (and cancel culture) of today.

“Some say that the ongoing activism around civil rights for Black Americans and tribal sovereignty for Native Americans are two different things that aren’t in solidarity,” Mays said. “But what I try to do in the book is use those two things as a jumping off point and say, if we look historically throughout U.S. history, how U.S. democracy was constructed and how even if these two groups often might have different goals, we see they still often collaborated. They both wanted a whole different understanding of what the U.S. could be.”

In the book, which is intended for a general audience, Mays said he wanted to offer readers a window into his process and what thoughts come up to him as a researcher and scholar.

“I try to blend the storytelling and nuance and argumentation of the historian, while also keeping my unique voice and reveal how I actually am thinking,” he said. “If we consider writing as a form of thinking and process, this is how I’m literally thinking about it in my head, and I want readers to hear that.”

From memories of the literature and teachers who inspired (and confounded) him during his academic career to moments with his teenage cousins “on the rez” watching impromptu rap battles, Mays’ narrative is infused throughout with his personal experiences as an Afro-Indigenous scholar, and his writing captures his purposeful language style.

“As a Black and Indigenous person, I suppose I’m just Mr. In-between, a brotha without a home,” he writes.

Released for Native American Heritage Month, “An Afro-Indigenous History of the United States” anchors an understanding of U.S. history on the twin atrocities fueled by settler colonialism and capitalism:

– the dispossession and attempted erasure of Indigenous peoples who lived on land now called the United States long before European ships set sail toward it;

– the enslavement of Indigenous Africans forcibly brought to these shores and whose bodies worked the land for the profit of others.

He critiques the racist underpinnings of early foundational texts, including the Declaration of Independence, and writings like “Democracy in America.”

“We must recognize antiblackness (and anti-Indianness, too!) as a core part of this country’s material and psychological development,” he writes. The book also illustrates how the parallel oppressions of Indigenous dispossession and anti-Blackness are ongoing.

Despite that continuing oppression, Mays offers the suggestion that we should think about how Indigenous Africans who were forcibly brought to and sold in America, still retained their inherent indigenous identities, similarly to how displaced Native tribes forced to reservations far from their ancestral territories retained their original tribal identities.

Expanding on and contextualizing the personal, Mays spotlights the history of collaboration between Blacks and Indigenous people. To do so, he combed through speeches and writings from revered Black writers, leaders and scholars such as Malcom X, Stokely Carmichael, Audre Lorde, Martin Luther King Jr., W.E.B. Du Bois as well as Native activists and writers such as Charles Eastman (Dakota), Laura Cornelius Kellogg (Oneida), Dennis Banks (Turtle Mountain Chippewa) and others, exploring how Black and Indigenous peoples have always resisted and struggled for freedom, sometimes together, and sometimes apart.

“I try to explore all those and just to say, ‘look, there have been forms of collaboration,’ but I always remind people, as I do in the book, that, as Audre Lorde told us, that solidarity is not easy,” he said. “Anything worth fighting for should not be easy. And we have to break down assumptions about what solidarity means and what that could look like. Hopefully I offered at least an entryway into exploring what relationships have looked like, are looking like now and what they can look like going forward.”

“An Afro-Indigenous History of the United States” requires readers to set aside preconceived ideas about what the United States is and what it might become. Mays argues that the enslavement of Africans and dispossession of Indigenous peoples were not necessary to the creation of an American democracy, but they were invaluable to the creation of wealth, property and the prestige of whiteness.

Mays said he hopes the book inspires in readers to take a more critical look at how the United States practices democracy and how it might evolve, and the pervasiveness of racism, even among and between groups that are most affected by it.

“It is important to really critically think about how we can all sort of reproduce racism, prejudice about other people,” he said. “But our job is also to try to overcome those things. And you need some form of solidarity to do so.”

This article originally appeared in the UCLA Newsroom. For more news and updates from the UCLA College, visit college.ucla.edu/news.

Photo credit: UCLA

Photo credit: UCLA Courtesy of Farwiza Farhan

Courtesy of Farwiza Farhan Photo credit: SPARC Archives/SPARCinLA.org

Photo credit: SPARC Archives/SPARCinLA.org