Pondering Peace: A Q&A with Professor Stella Ghervas

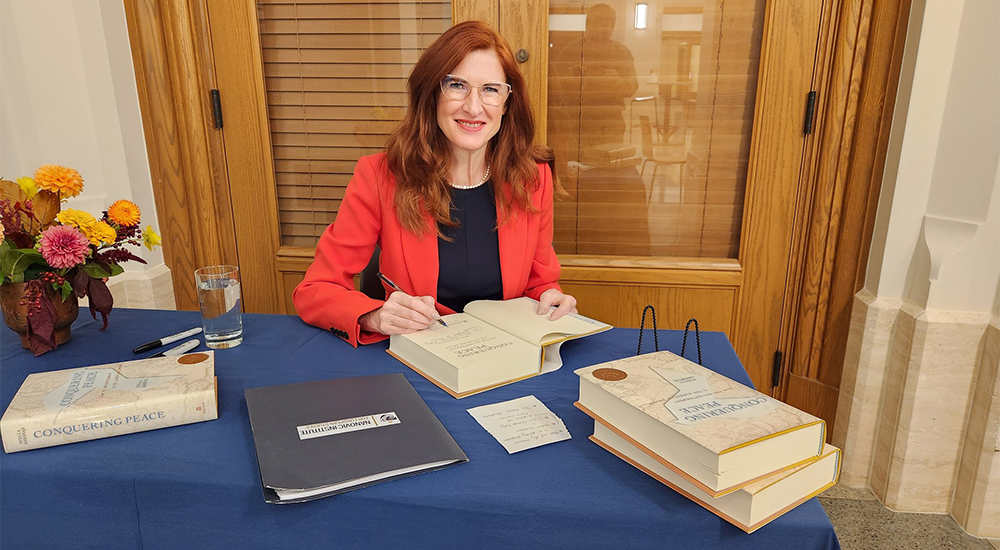

Keith Sayer / University of Notre Dame

Stella Ghervas, UCLA’s Eugen Weber Chair of Modern European History, won the 2023 Laura Shannon Prize in Contemporary European Studies for her book “Conquering Peace.”

By Jonathan Riggs | November 22, 2023

As impressive as 2023 has been for Stella Ghervas — not only did she win the Laura Shannon Prize in Contemporary European Studies for her acclaimed book “Conquering Peace,” but she also joined the UCLA faculty as the Eugen Weber Chair of Modern European History — in some ways, she’s looking forward to 2024 even more.

“I am excited to start teaching in the winter quarter of the new year,” said Ghervas, who has taught at ten universities, published six books and lived on four continents. “I would like to invite students from the Bruin community to join my courses and learn about the astonishingly fascinating history of Europe.”

We caught up with Ghervas to hear more about her work, her arrival at UCLA and what inspires her, both in and out of the classroom.

What inspired your award-winning book “Conquering Peace”?

Most history books tend to emphasize periods of war. They like to recount the past glory of empires, the deeds of generals and the great battles. Unsurprisingly, war stories and biographies of military figures like Nelson, Wellington or Montgomery sell well. The premiere of the new “Napoleon” biopic by Ridley Scott attests to this fascination. There is a good reason for this: Europe did have a violent past. After all, World War I and World War II both started there. Yet Europe has another gripping tale: this is how, after the guns fell silent, people of goodwill managed to rebuild a new political order from the rubble. And this slow and arduous process is what I call “Conquering Peace.”

My book offers a new history of Europe through the lens of peace and peace-making. It examines five pivotal moments, each characterized by its own unique “Spirit,” a spirit of peace, occurring shortly after a major geopolitical upheaval in which the continent narrowly averted the threat of a pan-European empire. These periods include Louis XIV’s bid for European hegemony (1701-1714), Napoleon and the French Empire (1799-1815), the German empires during the First (1914-1918) and Second World Wars (1939-1945), and Soviet hegemony over the eastern half of Europe during the Cold War (1947-1991).

In essence, my book unfolds as a historical panorama of peace in Europe spanning three centuries. It also shows how the evolution of the idea of Europe — cultural, economic and institutional — shaped the concept of peace. Instead of centering on war declarations or moments of conflict, I thus chose to highlight the intervals of relative calm that ensued: the birthing moments of peace. This turned out to be a profitable pursuit: peace treaties and peace conferences unfolded as suspenseful tales.

What intrigues you about this topic?

The reasons for my interest in the history of peace are both intellectual and personal. Of course, when we do an ex-post introspection on the origins of a book project, we discover that several motives were intertwined.

My initial interest was related to my previous research, which was on post-Napoleonic Europe and the new international order after the Congress of Vienna. I had published an earlier book in French, “Réinventer la tradition: Alexandre Stourdza et l’Europe de la Sainte-Alliance.” (An English edition is due from Cambridge University Press next year under the title “Enlightenment and Tradition in Post-Napoleonic Europe: The Worlds of Alexander Sturdza.”) It explored the intellectual climate and political conceptions in Europe during the Napoleonic and post-Napoleonic eras, through the eyes of an East-European character, Alexander Sturdza, who was a diplomat and writer in the service of Tsar Alexander I. I had investigated how the rulers and diplomats had managed to achieve peace after more than two decades of revolution and war; and how they had rebuilt the international order after the Congress of Vienna. As so often happens, I wished to explore these questions further and to expand my research in space and time — both backwards and forwards — and I finally covered more than three centuries of what I call the “engineering of peace” in Europe.

That’s very impressive.

But my interest in this topic actually goes further than that. I was born under the Soviet Union, in Bessarabia — today’s Republic of Moldova, a small state wedged between Romania and Ukraine. I used to spend my summer holidays in Odessa on the Black Sea. That region has been a hub of cultures for a long time, but also a hot spot for wars. As a child of perestroika, I enthusiastically embraced Gorbachev’s dream of a “common European home.” After all the dark years of the Cold War, it had left an indelible mark. Later, I moved to Switzerland: I became a citizen of that country and a resident of Geneva: a city that had seen the birth of the League of Nations and is today hosting many UN organizations. Hence, my turn to peace studies was also a tribute to my Swiss and Genevese identity.

You bring a remarkable scope of experience to UCLA, having held teaching, research and visiting positions in Australia, France, Georgia, Moldova, Romania, Russia, Switzerland, Ukraine, the U.K. and the U.S. How does having such a global perspective inform your work and your life?

My regional, European and global backgrounds informed both my research and teaching. As a historian of Europe, I naturally have a holistic vision of the “Old Continent.” This has been a through-line of my research over the past two decades as well as of my books.

My regional, European and global backgrounds informed both my research and teaching. As a historian of Europe, I naturally have a holistic vision of the “Old Continent.” This has been a through-line of my research over the past two decades as well as of my books.

Very often, when historians speak about Europe, they have the mental restriction of “the West,” going as far east as Germany but not further. I have a broader scope: from the Atlantic to the Ural Mountains, and from Cape North to the Strait of Sicily over the course of three centuries. And yes, that also includes Russia and the historical Constantinople (or Istanbul today). This perspective I refer to as “Enlarged Europe.” Seen in this enlarged perspective, the current European Union is merely the latest — and possibly not the last — of several attempts to achieve the “Idea of Europe” as a space of political peace.

“Europe” is furthermore a word of many definitions, depending on whether we look at it from a geographical, a political or a cultural perspective. The fact that a large part of the continent coalesced after the end of the Cold War into a European Union of 27 member states played, of course, a role. Today it is more necessary than ever to overcome previous political divisions (East-West) and to embrace this continent as one entity. The Russian invasion of Ukraine marks the return of conventional warfare to Europe just when a more durable peace hovered on the horizon. The new rift between Russia and NATO has created a balance of power that appears to be a relapse into older ways.

My teaching has also been inspired by my diverse cultural background. I’ve worked with both undergraduates and graduate students in a wide variety of environments. I’ve learned a lot about what works and what doesn’t. Peace turns out to be an attractive subject which can even provoke passions and vocations in my students.

What does it mean to you to hold the Eugen Weber Chair of Modern European History?

It is a special honor, which has a personal meaning to me. Like Professor Weber, the founder and the name of the chair, I was born in Eastern Europe, and like him, I have strong ties with Romania. His academic trajectory, which took him to France, then the United Kingdom and finally to the United States, is very similar to my own.

Here at UCLA, I am standing on the shoulders of giants. There are several decades of historic leadership in a department that once had the most prominent European history field in the country and one of the best in the world. The greatest figures of the department of history contributed with milestone works to the field of European history: Eugen Weber himself, Saul Friedlander, Carlo Ginzburg, Lynn Hunt and Perry Anderson, to mention just a few. This considerable legacy brings a lot of responsibility.

Today, Europe is going through its own specific existential crisis, which contains the revival of ethno-nationalisms, Britain’s exit from the European Union, a large influx of refugees, the social and economic consequences of the recent pandemic, divided emotions over recent events in the Middle East, and last but not least, Russia’s war of aggression in Ukraine. All this poses afresh the question of Europe as an international actor and as a continent of peace. The evolution of the field of European history reflects these deep transformations.

My vision consists of flinging open European history to the world, in a dynamic of inside-out and outside-in. Europe is certainly a geographically minute fraction of the planet, yet a densely populated, highly industrialized region in active interchange with the rest of the world. Its political place has evolved from being the motherland of commercial outposts and the seat of colonial powers to being a collection of “aligned” but demographically less significant states. Only by joining hands after World War II did they manage to return somewhat to the collective status of a great power.

How should Europe appear, from an African, Asian or American perspective? As a historian, I have been strongly challenging Eurocentric perceptions of the world in the same way that I have been challenging Western-centric perceptions of Europe. It is inspiring for me to find myself in a department that takes so seriously the most important new avenues of study, such as imperial and trans-imperial, colonial and post-colonial, maritime and oceanic, global and environmental, cultural and digital, legal and intellectual histories. Our graduate students need to be exposed more than ever to those diverse aspects, and our faculty will work with them to strengthen that sense of living within a global human community which has this in common — that it aspires to world peace.

What inspires you about being at UCLA?

Could we start with the amazing Southern California weather and the artistic center and cultural hub that is the city of Los Angeles? The Bruin community itself is exceptionally diverse: our students, staff and faculty members come from around the world. And believe me, I lived and worked on four continents and taught at 10 universities! The prestige of the UCLA Department of History and of the university in general is definitely another source of daily inspiration. I intend to carry further UCLA’s torch in my field (that is, beyond the 2028 Summer Olympics)!

Is there a little-known fact about yourself that we could share?

I am a lover of both peace and good chocolate. Europe is an exceptionally diverse continent. I like introducing my students to various aspects of European history, but also helping them to use their senses when learning about Europe. I enjoy cooking various European historical dishes for my friends and occasionally for my students — once, I even cooked one of the menus of the Congress of Vienna in 1814-15; and the Nesselrode pudding was a hit! I also hope that now that I work at UCLA and am so close to Hollywood, I should be able to find an excellent swing dance studio — and, one day, the time to play piano again.

What’s your favorite advice to give to your students?

When I first taught in the United States — at the University of Chicago — I had a revelation: I saw interested students who dared to speak up and were willing to ask pointed questions! This was very different from my own undergraduate experience in Europe. And I asked my students: What is Europe? What image does it evoke for you? How many European countries have you visited? How many languages do you speak? By their answers, I knew immediately we were starting a voyage of discovery together.

My favorite piece of advice to students has been the same: “Dare to think for yourself! Sapere aude!” This motto was used by the German philosopher Immanuel Kant in his essay “What is the Enlightenment?”, which is one of the works examined in my book “Conquering Peace.” Always have the courage to use your own judgement.

What would you like to say to UCLA students, present and future?

In the coming winter quarter, I will be giving my first lecture course on “War and Peace in Europe, 1700-1925.” In spring, I will hold my first undergraduate seminar, entitled “Russia and Ukraine: Roots of the Current Conflict” — anyone who wishes to understand the news will not want to miss that kind of background knowledge. At the beginning of the next academic year, I will offer a graduate seminar, “What is Europe? Politics, Power and Peace.”

In my teaching, I always attempt to mix research interests and use different approaches, including intellectual and international, legal and political, maritime and global history.

Welcome to my classes, Bruin students!