UCLA political scientists: Political polarization is not as simple as it appears

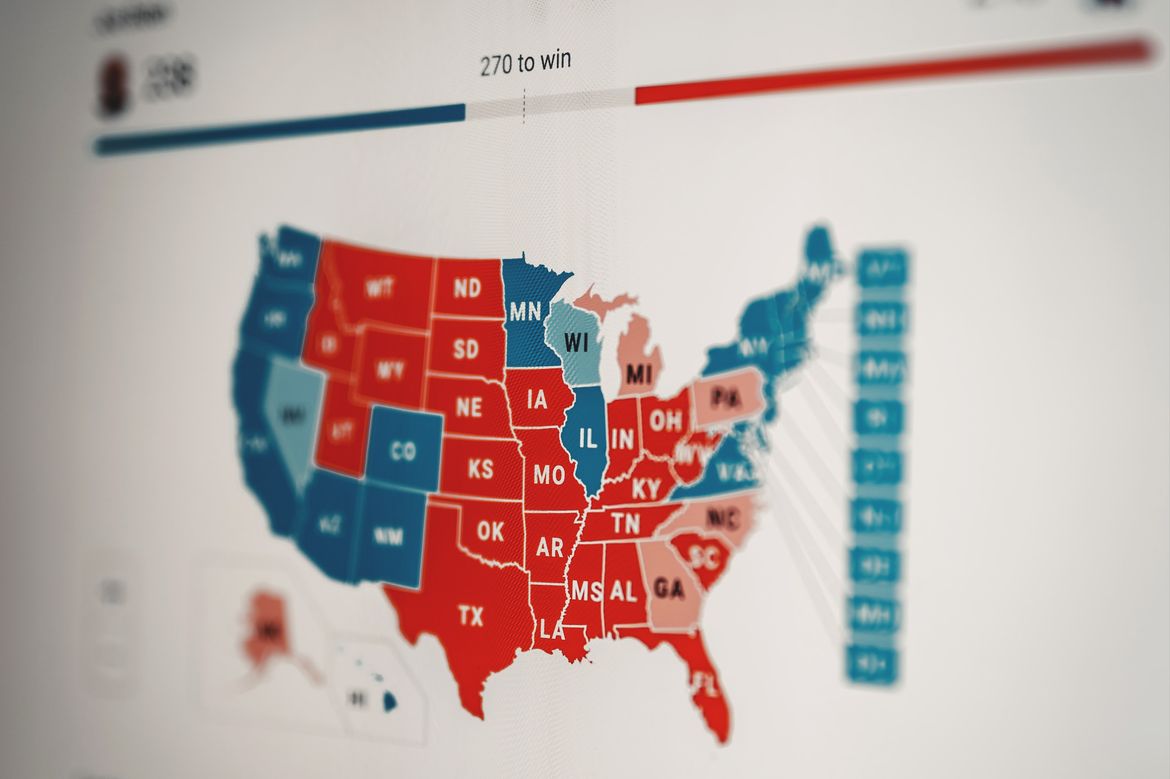

Electoral Map (Photo Credit: Clay Banks/Unsplash)

As President-elect Joseph Biden prepares to take office amid an era of intense partisanship, UCLA political scientists encourage people to adopt a different perspective on the country’s politically polarized landscape.

Lynn Vavreck, UCLA’s Marvin Hoffenberg Professor of American Politics and Public Policy, told the audience gathered for a “U Heard it Here” event on Nov. 17, that the emergence of more extreme differences among the public should not solely be attributed to the rise of social media or point-of-view-based cable news, which popularly get a lot of blame.

She and others who have been tracking voter attitudes for decades consistently find that voters tend toward confirmation bias.

“What people don’t understand about American politics is that voters always filter out information that is inconsistent with their prior views,” Vavreck said.

One thing that is definitely driving polarization is the behavior of elite politicians and the growth over the last two decades of more sophisticated and extremely well-funded campaigns.

These increasingly efficient campaign machines allow politicians to be more obstinate about compromise, even though large groups of voters in both parties might support an issue — like background checks on people who want to buy firearms or a path to citizenship for undocumented immigrants brought to the country as children, Vavreck said. Both of those things have broad support in both parties, but to differing levels of priority, she noted.

“You have two ways you can go; you can hold out or you can compromise,” she said. “If you compromise you might get some of what you want now, but if you hold out you can see if the power flips and then get everything you want.”

Efrén Pérez, professor of political science and director of the UCLA Race, Ethnicity and Politics Lab who also spoke on the panel, agreed.

“It’s important to contrast what is available for public consumption versus what we know as social scientists,” he said. “A lot of the divisiveness is really among the elites in the parties. There is an enormous sea of individuals for whom politics is kind of a colorful sideshow, they only sporadically interact with it.”

The resistance to compromise is with the power brokers in each party and depolarizing is about showing and convincing those same people that there is broad-scale agreement on some issues, he said. Biden might be able to use his long experience to find common ground on how to respond to the pandemic and heal the economy, something that will affect voters regardless of party preference.

Panelists, which also included UCLA political science professors Erin Hartman and Daniel Thompson, also talked about identity politics at play in 2020, how the pandemic and social justice affected campaign messaging, voter turnout, vote-by-mail and how pollsters fared this time around.

– It’s clear we need better polling of people of color to understand intersecting identities and priorities, Hartman said.

– We have to consider the multiple identities in the voting populace, beyond race, such as “occupational identities,” Pérez said. This likely came into play for Mexican-Americans in Texas border towns who responded to Trump’s law and order messaging because they or family members hold jobs in border patrol or law enforcement.

– Pollsters were right about a lot of things, like Georgia and Arizona being competitive and the way vote-by-mail would shake out by party.

– There were some interesting split votes that bear further consideration, Thompson said. Florida went for Trump, but voters there approved a $15 minimum wage, which was considered too far left for Hillary Clinton to endorse four years ago.

– The pandemic and the havoc it wreaked on the economy changed the Trump message, Vavreck said. Gross domestic product in the first six months of 2020 was dismal, hitting a post-New Deal low. But the stimulus checks meant household income was high, which helped turn out voters for Trump.

– Democrats leaned heavily into the message of social inequality, rising to the challenge of summer protests, and building on decades of effort to position the party as a broad home for voters of color, Pérez said.

This article, written by Jessica Wolf and Melissa Abraham, originally appeared in the UCLA Newsroom.