Thanks to family, graduating senior is driven to bridge cultural gaps

Growing up in Los Angeles, Priscilla Stephanie Molina would frequently go to work with her parents, doing homework while her mom cleaned houses or her father fixed someone’s leaky pipes. While some may have seen them as laborers, she saw leaders.

Priscilla Stephanie Molina (Photo Credit: Idriss Njike)

“My parents are both immigrants from Guatemala and I’m very proud of that,” said Molina, a first-generation college student graduating from UCLA June 12. “My mom runs her own housekeeping business. She has people who work for her and she organizes everything. My dad didn’t know much about plumbing, but he learned by working with his cousin, and then he started teaching people who now work under him.”

Whether at home, work or church, she saw her parents stepping in to lead the community and help those in need. Molina, who plans to attend medical school, has done the same at UCLA. She created cultural sensitivity training for her classmates before leading them on medical missions to Mexico, and she helped form a tutoring and mentorship program for K-12 students at her church who would be the first in their families to go to college. She served as a resident assistant for two themed floors in UCLA residence halls, helping build communities with activities like organizing empowering events for other first-generation college students one year, and cultural celebrations like a Dia de los Muertos event for the Chicanx/Latinx floor another year.

“My parents were a great example,” Molina said. “This is what we do. If my parents can lead, then I can, as well.”

Molina plans to become a psychiatrist so she can research and find better ways to support underserved communities that often lack psychiatric resources. Born and raised in Los Angeles’ San Fernando Valley, she’s seen how obstacles like language barriers, poor cultural awareness by doctors, and a lack of access can harm families. One of her older brothers was diagnosed with schizophrenia not long after she turned 10, and her parents didn’t know where to turn. Molina would join her mother at her brother’s doctor appointments to translate.

“They would give her information without explaining what it meant,” Molina said. “That has to change, and I want to help change it. We didn’t know what resources to connect to, what medicine to trust, or how to help my brother. I think a lot of that was because of cultural barriers. Public health, prevention and resources have to be culturally appropriate and meaningful to reach people. I want to be a doctor who is culturally sensitive.”

Molina’s sense of navigating and uniting two distinct worlds is apparent even in her name. Her parents and family friends know her by her middle name, Stephanie, while places that rely on registration forms use her first name, Priscilla.

“I always think of myself as Stephanie,” she said. “While Priscilla has always been my school-self. I enjoy it.”

By majoring in psychobiology and double-minoring in public health and in Latin American studies, Molina hopes to unite the three disciplines to address the problems she encountered growing up.

She already put her skills to use a few times with the Global Medical Missions Alliance. Her studies, combined with regular family summer trips to Guatemala, prepared her well to lead medical missions to Mexico. Though her friends in the university’s GMMA chapter prepared by studying Spanish, she didn’t see enough emphasis on learning about — and from — the people they were helping. She created cultural-sensitivity training for the group that was soon adopted by Global Medical Missions Alliance chapters in the United States, Australia and Canada.

“I wanted to emphasize how important it is to value the local people’s mindset, culture and knowledge, and not go in thinking we know better than they do,” Molina said. “There are things we can learn from them. The most important thing I advocated for was staying connected to the community’s leaders. They know best what their community needs.”

For her senior research project, she was able to combine all three of her academic interests in UCLA’s Psychology Research Opportunity Programs. Molina used a fotonovela, or graphic novel, in which a Latina character experiences symptoms of depression, and talks about it with her family and friends. She hoped that using this creative, culture-specific approach would make the Latino population she worked with more likely to seek out treatment themselves.

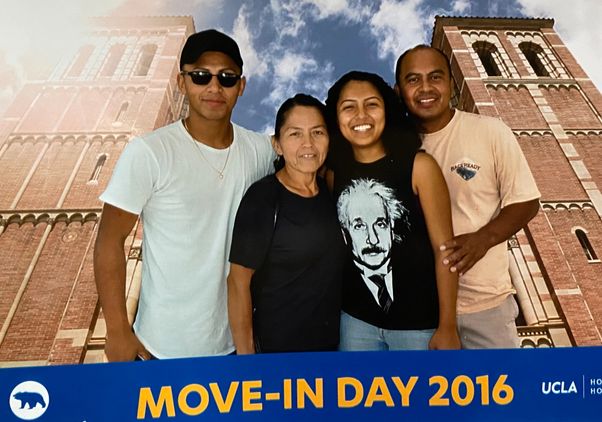

Courtesy of the Molina family

Her research found that people were more comfortable with the idea of seeking treatment if they had read the fotonovella showing someone from their culture. Unfortunately, she also found that readers with more barriers to mental health treatment still weren’t as likely to reach out for services as people who had fewer pre-existing barriers.

It’s an issue she hopes to research more. This summer, she has a paid position in a summer program with AltaMed Health Services, a health care provider that works in underserved communities. She hopes to either continue working with AltaMed or become an assistant resident director at UCLA while she takes some time off from school, and then apply to medical school.

Her parents always emphasized the importance of education, and encouraged her to think early on about a job that required education, she said.

“They always told me they didn’t want me to work a job the way they have to where they’re laborers,” she said. “And when I was little, I saw doctors as people who helped, and who made me feel better. So I wanted to be a doctor, but for a long time I didn’t really think I could.”

Living in the Valley, her schools had field trips to UCLA, and the university quickly became her goal. Though she’s disappointed that the current coronavirus pandemic and quarantine means there will be no graduation ceremony in Pauley Pavilion this June for her family to attend, she knows they are excited and proud of her for graduating.

“UCLA was my dream school,” Molina said. “I heard about all the optimistic goals. I knew I wanted to go into medicine, and you always hear that UCLA is one of the top schools for science and medicine and research. I felt like I belonged here. When I got in, it was a very happy moment for me and my family.”