UCLA historian Kelly Lytle Hernández awarded MacArthur Fellowship

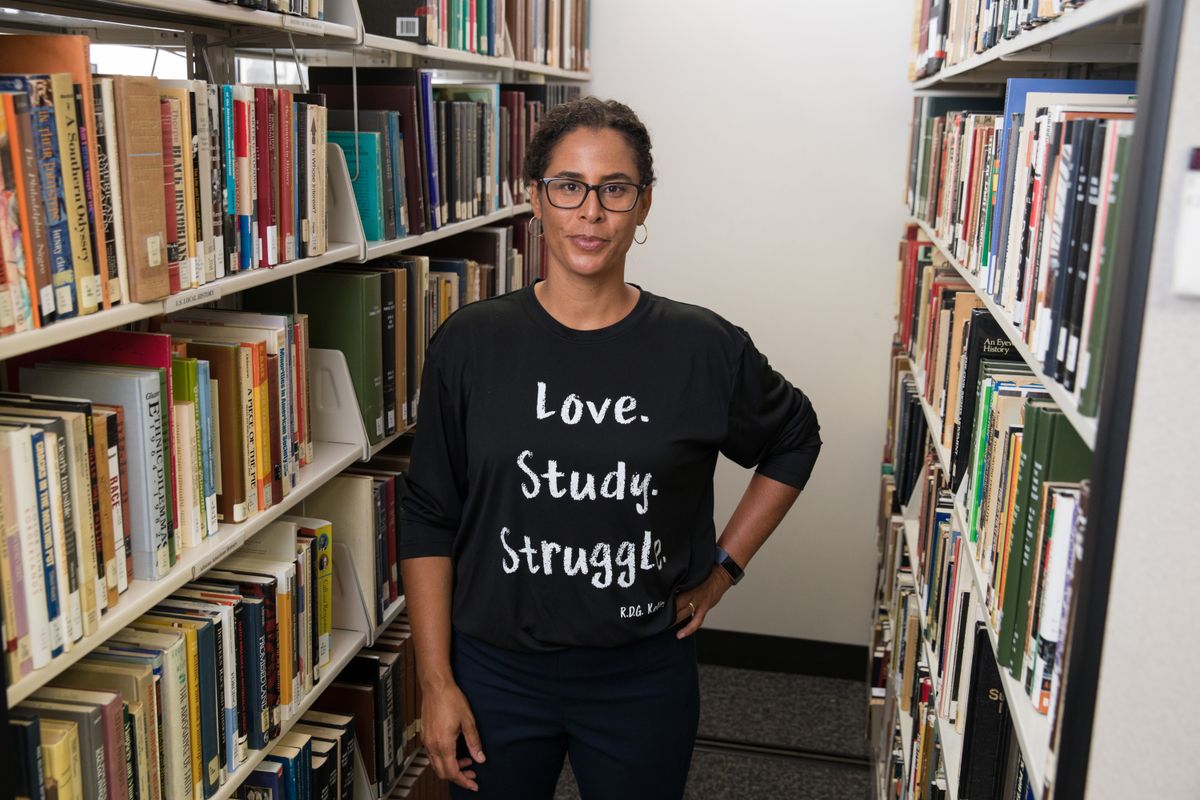

Kelly Lytle Hernández, a 2019 MacArthur Foundation Fellow, is one of 14 UCLA faculty to be chosen for the honor. Photo credit: John D. & Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation

UCLA professor Kelly Lytle Hernández, an award-winning author and scholar of race, mass incarceration and immigration, was announced today as a recipient of a prestigious MacArthur Fellowship from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation.

Lytle Hernández, who is a professor of history and African American studies, is the director of UCLA’s Ralph J. Bunche Center for African American Studies, which under her leadership has focused on supporting research into two critical themes in the modern black world — work and justice. The Bunche Center is home to Million Dollar Hoods, which maps the fiscal and human cost of mass incarceration in Los Angeles. Lytle Hernández is the director and principal investigator on the project.

“Lytle Hernández’s investigation of the intersecting histories of race, mass incarceration, immigration, and cross-border politics is deepening our understanding of how imprisonment has been used as a mechanism for social control in the United States,” the foundation said.

The MacArthur Fellowship is a $625,000, no-strings-attached award to people the foundation deems “extraordinarily talented and creative individuals.” Fellows are chosen based on three criteria: exceptional creativity, promise for important future advances based on a track record of accomplishments, and potential for the fellowship to facilitate subsequent creative work. Lytle Hernández is one of 26 individuals the foundation selected for fellowships in 2019.

“As a scholar, I both work deeply alone and deeply in community, but until very recently the scholarly communities I’ve worked in — immigration and the carceral state — have been fairly separate,” said Lytle Hernández, who holds the Thomas E. Lifka Chair in History at UCLA. “I hope my work has helped people understand immigration as another aspect of mass incarceration in the United States and that my award further helps people understand that these two regimes are intertwined. This award will help us continue this work across communities and shine a light on this kind of thinking that unites these two crises that others often see as distinct.”

Lytle Hernández, 45, received a her bachelor’s degree from UC San Diego in 1996 and earned her doctorate in 2002 from UCLA.

For her first book, “MIGRA! A History of the U.S. Border Patrol,” Lytle Hernández pored over historical records to illuminate the border patrol’s nearly exclusive focus on policing unauthorized immigration from Mexico.

In “City of Inmates: Conquest, Rebellion, and the Rise of Human Caging in Los Angeles,” she began zeroing in on another dimension of race and law enforcement, specifically what forces shaped Los Angeles so that it came to operate the largest jail system in the United States.

“What I found in the archives is that since the very first days of U.S. rule in Los Angeles — the Tongva Basin — incarceration has persistently operated as a means of purging, removing, caging, containing, erasing, disappearing and otherwise eliminating indigenous communities and racially targeted populations,” Lytle Hernández said in an interview about the book.

The MacArthur Fellowship, which is commonly referred to as the “genius grant,” is according to the foundation, intended to encourage people of outstanding talent to pursue their own creative, intellectual and professional inclinations. Recipients may be writers, scientists, artists, social scientists, humanists, teachers, entrepreneurs, or those in other fields, with or without institutional affiliations.

Lytle Hernández joins 13 other UCLA faculty as MacArthur fellows, including mathematician Terence Tao, choreographer Kyle Abraham, director Peter Sellars, astrophysicist Andrea Ghez and historian of religion Gregory Schopen.

While unsure of her specific plans for the award, Lytle Hernández said that she will continue to expand the scope and scale of her social justice scholarship, including with partners outside of UCLA.

“I’d like to create a space for myself and others — especially community organizers and movement-driven scholars — to write,” she said, noting that these people’s calendars tend to be jammed by the “urgency of their work.” “I’d like to create space that allows myself and others to process the work that we’re doing and to share it.”

This article originally appeared in the UCLA Newsroom.