Will ocean seafood farming sink or swim? UCLA study evaluates its potential

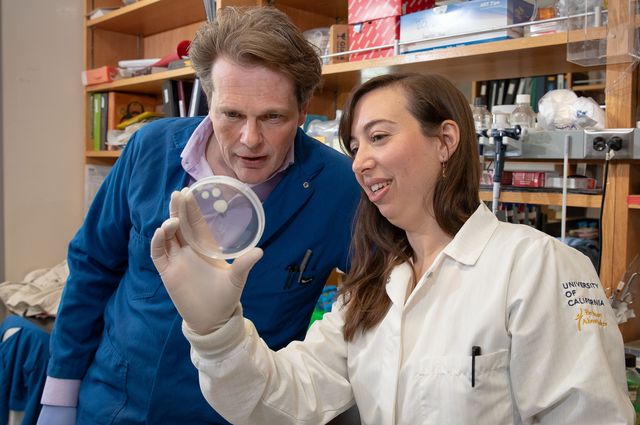

Divers survey submersible cages used to farm cobia off the coast of Puerto Rico. UCLA researchers conducted the first country-by-country evaluation of the potential for marine aquaculture under current policies and practices.

Seafood farming in the ocean — or marine aquaculture — is the fastest growing sector of the global food system, and it shows no sign of slowing. Open-ocean farms have vast space for expansion, and consumer demand continues to rise.

As with many young industries, there’s a lot to figure out, from underlying science and engineering to investment and regulations.

In a study published in the journal Marine Policy, UCLA researchers report that they have conducted the first country-by-country evaluation of the potential for marine aquaculture under current governance, policy and capital patterns. They discovered a patchwork of opportunities and pitfalls.

Peter Kareiva, one of the study’s authors and director of the UCLA Institute of the Environment and Sustainability, said sustainable food systems are an important part of the fight against climate change.

“Like many environmental scientists, I see marine aquaculture as the future food system for a carbon neutral world,” Kareiva said. “But whether we get that future and a healthy ocean depends on governance and regulations — and we all know how sketchy those can be at times.”

In 2017, Kareiva’s research found that a tiny fraction of the world’s oceans, farmed sustainably — just 0.015 percent — could satisfy the entire world’s fish demand.

The new study categorizes 144 countries into three groups based on their capacity for aquaculture growth in the industry: “goldilocks,” “potential at-risk” and “non-optimized producer.” The categories are based on quality of government institutions and regulations, potential for investment and how suitable the biological and physical environment are for farming seafood in the ocean.

Sixty-seven countries fell in the goldilocks category for either finfish or bivalves, like mussels and clams — meaning conditions there are favorable for marine aquaculture. According to lead author Ian Davies, who conducted research for the study at Kareiva’s UCLA lab, the industry could help address social challenges in these places.

“There is a lot of potential in food-insecure countries, including island states in the Pacific and Caribbean,” Davies said. “They have limited resources and quickly growing populations. But these are also the countries with the most productive waters in the world.”

Twenty-four countries were identified as non-optimized producers, which lack highly productive waters but still engage in aquaculture, usually because of better access to investment. This group includes countries around the Persian Gulf and Black Sea, South Korea, Italy, Canada and Norway.

Finally, the paper categorized 77 countries as potential at-risk. These countries have suitable waters but poor access to capital and unstable, corrupt or ineffective governance systems. Despite such problems, 16 are currently farming fish in the ocean, often harming ecosystems or causing other problems in the process. China is by far the largest producer of ocean-farmed seafood, owing to strong financial capacity and political will, but was found to have poor oversight — which could pose problems for the industry in the future.

“The more robust regulation you have, the more you can ensure the industry will be around for longer, and that it will be able to produce fish at a reasonable cost with minimal input,” Davies said. “There is a palpable feeling among planners, researchers and aquaculture operators that we have the ability to do this right before the industry gets too big. Let’s put the regulations in place.”

Ineffective regulation often leads to ecosystem damage. In the 1990s, there was a shrimp farming boom in Southeast Asia. Operations added too much shrimp and feed to mangroves, destroying many in the process. The impact was also felt by humans. Mangroves serve as barriers that reduce storm surge and flooding, and many small aquaculture operators quickly found themselves out of business. More recently, unregulated fish farming led to disease outbreaks in northern Vietnamese waters.

In other observations, the study found that while lack of regulation poses problems, so can regulation that is too burdensome. In Ireland the licensing process takes years, making it impossible for operators to qualify for European Union grants. There are other country-specific barriers, too. New Zealand is a goldilocks country, but opposition from local communities and vocal stakeholders, including fishermen, has slowed marine development.

China is the largest marine aquaculture producer by far, but its waters are only moderately good and its governance was listed as low quality. The industry has succeeded there because of political will and access to capital. China isn’t alone. Excluding outliers, the study notes, less suitable countries produce almost six times as much fish as optimal countries. Capital-driven aquaculture in less suitable waters carries the risk of being less effective and more damaging.

Marine aquaculture is seen as promising compared to high-polluting inland operations. The open ocean disperses its impact, leading to fewer environmental problems. Meanwhile, according to the United Nations, nearly 90 percent of the world’s marine stocks are depleted, with many fisheries on the verge of collapse. Sustainably farming oceans could allow wild populations to rebound while serving as a crucial source of protein and economic benefits to humans.