New center at UCLA raises everyone’s voices for environmental science

The campus is home to the first university-based center dedicated to diversity in the field.

The campus is home to the first university-based center dedicated to diversity in the field.

By Rayna Jackson

Nasim Andrews knew exactly what she wanted to do when she was 10 years old: become a doctor. This small town girl from Los Alamos, New Mexico, had a plan. First, get into UCLA. Second, take every pre-med course, extracurricular activity and program that would get her closer to her dreams.

“Anyone who knew me at the beginning of my college career can tell you that I wanted to be a doctor,” recalled Andrews, who just graduated from UCLA with a bachelor’s degree in human biology and society. “I thought that the best way to make an impact on people’s lives was through medicine.”

Andrews didn’t realize it at the time, but now looking back at her academic career, she recognizes that she was about to have a ‘life-changing’ experience. Her major introduced her to “Perspectives on Disability Studies” as one of the electives she could take. After completing the class, Andrews says that her whole mindset about disability changed. She began to question concepts about ‘normalcy’ in society and began to look at her own perceptions about ability.

“A minor in disability studies signals to a potential employer that this applicant brings an intellectual perspective to the many issues of access and inclusion that are ubiquitous in 21st century workplaces,” said Patricia Turner, dean and vice provost of undergraduate education. “Beyond that, it is a great example of how UCLA embraces teaching innovation and applies contemporary societal issues to create a vibrant curriculum for our students.”

Since the disability studies minor began a decade ago, the class topics and discussions have created buzz among students. The result is that students’ level of interest has increased. The first disability studies course enrolled only a handful of students. Now there are more than 36 courses offered annually and more than 400 undergraduates enroll in disability studies courses each year. The minor has also graduated more than 100 students.

Nasim Andrews ’17 says that being part of UCLA’s disability studies program was a “life-changing” experience.

Disability activism

One out of five people, or 56.7 million Americans, have a disability, according to the 2010 U.S. census. As the number of people with disabilities increases, there is a growing national and global movement to understand and accept disability.

UCLA students who are a part of disability studies take their new understanding and become disability advocates in their own sphere of influence. In the last decade, students have completed close to 25,000 service hours through the minor, benefiting 36 local, state and national organizations that work directly with disabled communities.

“We have the opportunity to change our built environment, our policies and our laws,” chair of disability studies Vic Marks said. “That is to say that we can be change makers within our own lives, our families and in our larger community. Disability studies students do this every day.”

Disability studies also gives students the opportunity to practice disability activism through the lens of philanthropy. Last spring, students had the rare opportunity to distribute a $75,000 grant to local nonprofits that served people with disabilities through the philanthropy course “Confronting Challenges of Serving the Disabled.”

In the philanthropy course, students had to collectively decide how to distribute grant monies to local nonprofits that served people with disabilities. They researched 20 local organizations, made site visits, developed requirements and a process for funding, and then negotiated who the awardees would be and how the funds would be distributed.

Shane’s Inspiration, a local nonprofit organization that designs and develops inclusive playgrounds and educational programs to unite children of all abilities, received $25,000 from the philanthropy course. The investment will allow the organization to reach more students and educators within the Los Angeles community. Additionally, Shane’s Inspiration has been able to use the grant monies to expand its reach into higher education.

Andrews was among the students in the philanthropy course that awarded grant money to Shane’s Inspiration. She immediately saw the importance of their work with children. Andrews quickly became the nonprofit’s biggest advocate in class and even sought an internship opportunity with the organization. Both the class and her work at Shane’s Inspiration prompted her to think differently about her lifelong goal of becoming a doctor.

“I would always say, ‘When I grow up I want to go to work as a doctor and know that I am making an impact on somebody’s life,’” Andrews said. “To get that same feeling from being on the playground at Shane’s Inspiration was the exact same feeling I was looking for.”

Tiffany Harris, CEO and co-founder of Shane’s Inspiration, believes that the disability studies program gives students like Andrews the opportunity to challenge misconceptions about disabilities,

Andrews (left) with families at Shane’s Inspiration site in Anthony C. Beilenson Park in Los Angeles. UCLA disabilities studies students awarded a grant to Shane’s Inspiration through the philanthropy course “Confronting Challenges of Serving the Disabled.”

which in turn will allow them to be better at their chosen profession.

“Every one of us within our lifetime is going to be in a position to interface with someone with a disability, or perhaps face a disability ourselves,” Harris said. “By having access to a class like this, students are able to expand their understanding of their perceptions of people with disabilities, and by doing so, create a new opportunity for connection in the future.”

After years of planning her life, Andrews did not graduate as a pre-med student. She wouldn’t have it any other way.

“Joining the minor was one of the best decisions that I made while at UCLA,” Andrews said. “There is no doubt that the classes and experiences in the minor helped me to learn more about myself and helped me realize that even with my diverse interests, I can have an impact in people’s lives.”

Andrews now combines her passion for health care with her passion and understanding of disability in a new role with Triage Consulting Group in San Francisco.

Expanding the global reach of disability studies

In a milestone for the program, disability studies marked its 1-year anniversary in April by hosting UCLA’s first international conference, “Disability as Spectacle.” The conference brought together thought leaders from the United Kingdom, Taiwan, South Africa, India, Malawi, Sweden and the United States to examine how spectacle can be used as a tactic for social change.

As disability studies continues to grow, more attention will be brought to the vibrant nature of the program both locally and abroad. And undoubtedly, like Andrews, more students will have “life-changing” experiences through the disability studies program at UCLA.

Learn more:

http://www.uei.ucla.edu/dsminor.htm

The road to gender balance among tenure-track faculty

By Jessica Wolf

At UCLA and across the nation, expanding the pipeline of graduate students to be more reflective of our diverse society will transform university research and teaching, according to several campus leaders. In terms of gender balance, progress continues, with women now earning more than half of all doctoral degrees nationally over the past decade, according to the American Council on Education.

Laura Gómez

Gradually, women are also catching up among the ranks of tenure-track faculty. As of 2014, women make up more than 37 percent of tenure-track faculty at all American postsecondary institutions, according to the National Center for Education Statistics.

Yet this statistic masks significant differences among types of institutions, disciplines and levels of seniority. For example, at most universities (and especially at research universities), there are relatively small proportions of female faculty at the full professor level (which is typically achieved after 12 or more years on the tenure track) and larger proportions at the assistant professor level, reflecting the growth in the number of female Ph.D. students. Within the UCLA College, three of four divisions–social sciences, humanities and life sciences–have proportions of women among tenure-track faculty that exceed the national average, according to the UCLA Office of Equity, Diversity & Inclusion.

“We’ve made great strides in the United States in reaching gender parity in rates of college graduation and, especially in the humanities and social sciences, in rates of Ph.D. completion,” said Laura E. Gómez, who just completed a term as interim dean of social sciences, the first woman to head that division.

“UCLA’s Ph.D. students are tomorrow’s professors,” Gómez said. “So diversifying the ranks of our graduate students is a high priority if we are to continue the progress made over the past several decades.”

UCLA’s social sciences division is home to nine Ph.D.-granting departments, with the share of female graduate students ranging from a high of 97 percent in the gender studies department to a low of around 20 percent in economics. In almost every field of study, the proportion of female faculty has grown dramatically since the 1980s, but there is still plenty of room for improvement.

Pathways to leadership

Nancy Levine

While there are now more female faculty members throughout the division, long-established departments such as anthropology, economics, political science and sociology have only recently been chaired by women for the first time. Generally limited to full professors, serving as chair is virtually a prerequisite for top leadership roles such as dean, provost and university president.

Consider anthropology, which used to be dominated by male professors and male graduate students. When she was a graduate student in the late 1970s, Nancy Levine, who just completed a four-year term as chair of the anthropology department, said she could count on one hand the number of women in her doctoral cohort as well as on the UCLA faculty when she joined it.

Today, women are 50 percent of all tenured and tenure-track professors in the department. In addition, from 2005 to 2015, women were 67 percent of all recipients of anthropology Ph.D.s at UCLA, compared with 61 percent nationally, according to the National Science Foundation.

A closer look at the dynamics

Having women in each field not only has an impact on research and teaching, but also plays a subtle and positive role in the ethos of a department and how students maintain support systems during what can be a very grueling time in their lives, said Barbara Geddes, who is the first woman to chair the political science department.

Currently, about a quarter of UCLA’s political science faculty are female, comparedwith 37 percent of political science professors nationwide. From 2005 to 2015, 39 percent of doctoral recipients in the department were women, versus 41 percent nationally.

According to Geddes, there has traditionally been a divide in political science: research and courses heavily related to mathematics, statistics and data generally are taught and pursued by men, while women fall into the more humanities-driven areas, such as comparative politics, where Geddes, a scholar of Latin American politics, focuses. Geddes said she sees the lines starting to blur along this front, with more women teaching and conducting research in statistically based sub-fields.

Getting young women interested very early in data, math and statistics may be the best way to bridge the persistent gender gap in economics, said economics professor Adriana Lleras-Muney, who for three years has led her department’s faculty hiring efforts.

During the period 2005-2015, women made up 31 percent of the doctoral recipients in economics at UCLA, on par with the national trend.

Kathleen McGarry

Kathleen McGarry, who recently completed four years as the first female chair of economics, noted that now “nearly 50 percent of our students are women, a percentage that is among the highest of any major university.”

She said this trend bodes well for the academic pipeline, suggesting that today’s economics undergraduates will become tomorrow’s Ph.D. students and, eventually, professors. Moreover, while economics has fewer women faculty than several departments in the social sciences at UCLA, it boasts a greater percentage of female faculty than nearly all of the other top 20 economics departments in the country.

The next generation

Sociology professor Judith Seltzer, who joined the faculty 20 years ago, recalled, “When I first arrived at UCLA, one of my senior colleagues, a very distinguished sociologist of women’s employment, told me that when she joined the faculty, it was so unusual for a woman to be a professor that people often thought she was a secretary for her male colleagues. That mistake would not happen today.”

Today, almost 40 percent of sociology’s tenure-track faculty at UCLA are women, and the number of female Ph.D. recipients in recent years has been on par with the proportion nationally, at around 62 percent.

Sociology professor Vilma Ortiz, who is frequently sought out as a mentor by female doctoral students and especially by women of color, applauds UCLA’s Office of Equity, Diversity & Inclusion for raising awareness about the role unconscious bias may play in the faculty hiring process. She noted, however, that creating a more diverse pool of faculty candidates must start even earlier by recruiting women, minorities and first-generation college students into Ph.D. programs and ensuring they receive great mentoring throughout graduate school.

Gómez agreed, noting as well the powerful influence of role models in the undergraduate classroom.

“It makes an incredible difference for a young woman to see someone like herself standing at the head of the class,” Gómez said. “It allows her to imagine herself in the same position one day.”

By Stuart Wolpert

The hit Disney movie Moana features stunning visual effects, including the animation of water to such a degree that it becomes a distinct character in the film. A senior software engineer at Walt Disney Animation Studios, Alexey Stomakhin M.A. ’11, Ph.D. ’13, led the development of the code used to simulate the movement of water in the movie.

They infuse the magic of realism in animation and apply knowledge to solve real-world problems

UCLA mathematics professor Joseph Teran, a Walt Disney consultant on animated movies since 2007, is under no illusion that artists want lengthy mathematics lessons, but many of them realize that the success of animated movies often depends on advanced mathematics.

“In general, the animators and artists at the studios want as little to do with mathematics and physics as possible, but the demands for realism in animated movies are so high,” Teran said. “Things are going to look fake if you don’t at least start with the correct physics and mathematics for many materials, such as water and snow. If the physics and mathematics are not simulated accurately, it will be very glaring that something is wrong with the animation of the material.”

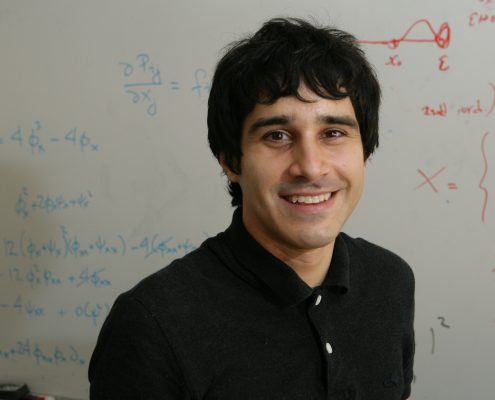

Joseph Teran

Teran and his research team have helped infuse realism into several Disney movies, including Frozen, where they used science to animate snow scenes. Most recently, they applied their knowledge of math, physics and computer science to enliven the 3-D computer-animated hit Moana, a tale about an adventurous teenage girl who is drawn to the ocean and is inspired to leave the safety of her island on a daring journey to save her people.

Teran’s former doctoral student, Alexey Stomakhin, played an important role in the making of Moana. After earning his Ph.D. in applied mathematics in 2013, he became a senior software engineer at Walt Disney Animation Studios. Working with Disney’s effects artists, technical directors and software developers, Stomakhin led the development of the code that was used to simulate the movement of water in Moana, enabling it to play a role as one of the characters in the film.

“The increased demand for realism and complexity in animated movies makes it preferable to get assistance from computers; this means we have to simulate the movement of the ocean surface and how the water splashes, for example, to make it look believable,” Stomakhin explained. “There is a lot of mathematics, physics and computer science under the hood. That’s what we do.”

Moana has been praised for its stunning visual effects in words the mathematicians love hearing.

“Everything in the movie looks almost real, so the movement of the water has to look real too, and it does,” Teran said. “Moana has the best water effects I’ve ever seen, by far.”

Building your own universe with math

Stomakhin said his job is fun and “super-interesting, especially when we cheat physics and step beyond physics. It’s almost like building your own universe with your own laws of physics and trying to simulate that universe.

“Disney movies are about magic, so magical things happen which do not exist in the real world.”

Added the software engineer, “It’s our job to add some extra forces and other tricks to help create those effects. If you have an understanding of how the real physical laws work, you can push

parameters beyond physical limits and change equations slightly; we can predict the consequences of that.”

To make animated movies these days, movie studios need to solve, or nearly solve, partial differential equations. Stomakhin, Teran and their colleagues build the code that solves the partial differential equations. More accurately, they write algorithms that closely approximate the partial differential equations because they cannot be solved perfectly.

“We try to come up with new algorithms that have the highest-quality metrics in all possible categories, including preserving angular momentum perfectly and preserving energy perfectly. Many algorithms don’t have these properties,” Teran said.

Stomakhin was also involved in creating the ocean’s crashing waves that have to break at a certain place and time. That task required him to get creative with physics and use other tricks. “You don’t allow physics to completely guide it,” he said.

“You allow the wave to break only when it needs to break.” Depicting boats on waves posed additional challenges for the scientists.

“It’s easy to simulate a boat traveling through a static lake, but a boat on waves is much more challenging to simulate,” Stomakhin said. “We simulated the fluid around the boat; the challenge was to blend that fluid with the rest of the ocean. It can’t look like the boat is splashing in a little swimming pool — the blend needs to be seamless.”

Stomakhin spent more than a year developing the code and understanding the physics that allowed him to achieve this effect.

“It’s nice to see the great visual effect, something you couldn’t have achieved if you hadn’t designed the algorithm to solve physics accurately,” said Teran, who has taught an undergraduate course on scientific computing for the visual-effects industry.

Alexey Stomakhin

From silver screen to surgery

While Teran loves spectacular visual effects, he said the research has many other scientific applications as well. It could be used to simulate plasmas, to simulate 3-D printing or for surgical simulation, for example. Teran is using a related algorithm to build virtual livers to substitute for the animal livers that surgeons train on. He is also using the algorithm to study traumatic leg injuries.

Teran describes the work with Disney as “bread-and-butter, high-performance computing for simulating materials, as mechanical engineers and physicists at national laboratories would. Simulating water for a movie is not so different, but there are, of course, small tweaks to make the water visually compelling. We don’t have a separate branch of research for computer graphics. We create new algorithms that work for simulating wide ranges of materials.”

Teran, Stomakhin and three other applied mathematicians — Chenfanfu Jiang, Craig Schroeder and Andrew Selle — also developed a state-of-the-art simulation method for fluids in graphics, called APIC, based on months of calculations. It allows for better realism and stunning visual results. Jiang, a UCLA postdoctoral scholar in Teran’s laboratory, won a 2015 UCLA best dissertation prize. Schroeder is a former UCLA postdoctoral scholar who worked with Teran and is now at UC Riverside. Selle, who worked at Walt Disney Animation Studios, is now at Google.

Their newest version of APIC has been accepted for publication by the peer-reviewed Journal of Computational Physics.

“Alexey is using ideas from high-performance computing to make movies,” Teran said, “and we are contributing to the scientific community by improving the algorithm.”

By Stuart Wolpert

Consuming fructose, a sugar that’s common in the Western diet, alters hundreds of brain genes that may be linked to many diseases, UCLA life scientists report. However, they discovered good news as well: an important omega-3 fatty acid known as DHA (docosahexaenoic acid) seems to reverse the harmful changes produced by fructose.

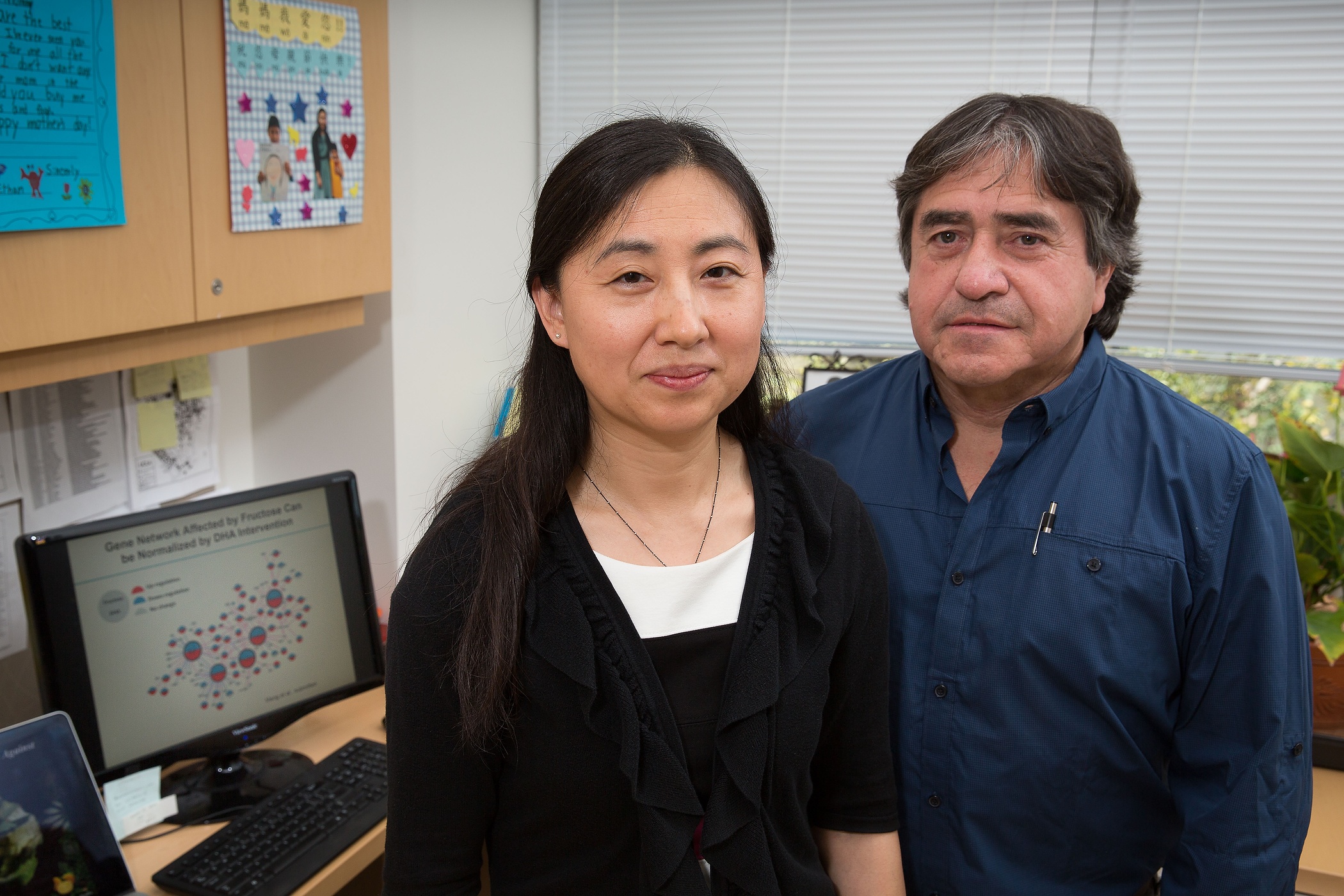

“DHA changed not just one or two genes, but seems to push the entire gene pattern back to normal, which is remarkable, and we can see why it has such a powerful effect,” said Xia Yang, a senior author of the study and a UCLA associate professor of integrative biology and physiology.

DHA is found in brain cell membranes, but “the brain and the body are deficient in the machinery to make DHA; it has to come through our diet,” said co-senior author Fernando Gomez-Pinilla, a UCLA professor of neurosurgery and of integrative biology and physiology.

DHA, which strengthens synapses in the brain and enhances learning and memory, is abundant in wild salmon and, to a lesser extent, in fish oil and other fish, while its biochemical precursors are high in walnuts, flaxseed, and to a less extent, fruits and vegetables, Gomez-Pinilla said.

Americans consume most of their fructose from processed foods sweetened with high-fructose corn syrup, an inexpensive liquid sweetener made from cornstarch, as well as from sweet drinks, syrups, honey, ice cream and other desserts, he said. It’s also in baby food. Fruit contains fructose, but has high levels of fiber, which substantially slows the absorption of fructose and increases the feeling of fullness, Yang said. Fruits also contain many other healthy components that protect the brain and body, they noted.

Lab-tested

The researchers trained laboratory rats to escape from a maze, then randomly divided the rats into three groups. They gave one group of rats water with fructose added for six weeks that would be roughly equivalent to a person drinking about a liter of soda a day. A second group of rats was given the water with fructose and a diet rich in DHA for six weeks, and a control group was given water without fructose and not given the DHA supplement.

The rats that had been given the fructose had significantly higher blood glucose, triglycerides and insulin levels than the control group, and had impaired memory when navigating the maze; they were about 30 percent slower than the control group in escaping from the maze. The rats given the

DHA supplement, however, showed very similar results to the control group.

Yang and Gomez-Pinilla’s research team sequenced more than 20,000 genes in the rats, and discovered that fructose adversely affected more than 700 genes in the hypothalamus and more than 200 genes in the hippocampus – genes that interact to regulate metabolism, cell communication and inflammation.

Xia Yang and Fernando Gomez-Pinilla

Humans have genes that are counterparts to the genes affected by fructose in rats, and the human genes are associated with obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, depression, bipolar disorder, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and other brain diseases, said Yang, a member of UCLA’s Institute for Quantitative and Computational Biosciences.

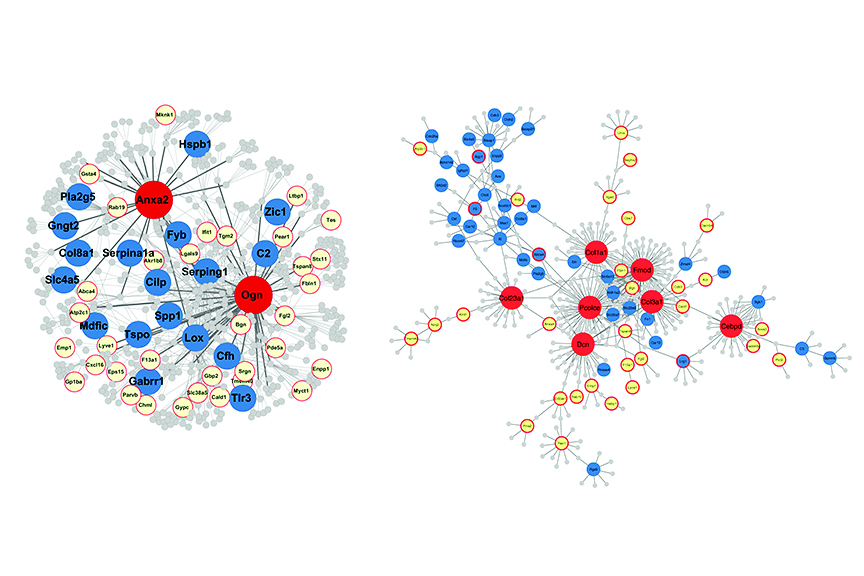

The researchers identified two genes, called Bgn and Fmod, that are important for cell communication, and are potential targets for new pharmaceuticals. Fructose seems to act first on these genes, which then affect many other genes, in a cascade effect, Yang said. After the researchers removed these genes in mice, the mice had substantially higher levels of cholesterol and triglycerides.

The research, which used state-of-the-science genomic technology, was published last year in the journal EBioMedicine.

This research is the first comprehensive genomics study of all the genes, pathways and gene networks affected by high fructose consumption in brain regions controlling metabolism and brain function.

How food affects the brain

Fructose damages communication between brain cells, and increases toxic molecules in

the brain, Gomez-Pinilla’s research team reported in 2015. Earlier research has demonstrated how fructose contributes to cancer, diabetes, obesity and fatty liver.

Gomez-Pinilla recommends reducing the sugar and saturated fat we consume, including reducing drinking soda and eating dessert. “Food is like a pharmaceutical compound that affects the brain,” said Gomez-Pinilla, also a member of UCLA’s Brain Injury Research Center.

Co-authors include lead author Qingying Meng, a postdoctoral scholar in Yang’s laboratory; Zhe Ying, a staff research associate in

Gomez-Pinilla’s laboratory; and colleagues from UCLA, the National Institutes of Health and Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York.

Ties to head trauma

In February 2017, Yang, Gomez-Pinilla and colleagues reported in EBioMedicine that head injuries can adversely affect hundreds of genes in the brain that put people at high risk for diseases including Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s,

Examples of gene networks in the hippocampus affected by brain trauma. UCLA researchers report that the “master regulator” genes (in red) influence many other genes responsible for the effects of brain trauma.

post-traumatic stress disorder, stroke, ADHD, autism, depression and schizophrenia.

“Very little is known about how people exposed to brain trauma, such as football players and soldiers, develop symptoms for other neurological disorders later in life. We hope to learn much more,” Gomez-Pinilla said.

The researchers have identified for the first time potential master genes, which they believe control hundreds of other genes that they linked to many neurological and psychiatric disorders. These master genes are likely targets for new pharmaceuticals to potentially treat many diseases of the brain.

“We believe these master genes are a kind of hub responsible for traumatic brain injury adversely triggering changes in many other genes,” Yang said.

Traumatic brain injury can do damage first to the master genes and then to other “downstream genes” in a couple of ways, she said. One way is to produce different forms of a protein. Another is to reduce, or increase, the number of expressed copies of a gene in each cell. Both can prevent a gene from properly performing its cellular function.

“If a gene turns into the wrong form of protein, it could lead to Alzheimer’s disease, for example,” Gomez-Pinilla said.

Implications for treating a range of diseases

More than 100 of the genes that changed following the brain injury have human counterparts that have been linked to Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, ADHD and other neurological and psychiatric disorders, the researchers report.Targeting these genes to treat disease seems promising. “We now know which genes are affected by traumatic brain injury and linked to serious disease, and have predicted which genes are the likely master regulators that may have strong therapeutic potential,” Yang said.

The research team is further studying whether modifying some of the master genes also modifies large numbers of other genes. If so, then targeting the master genes will be even more promising.

One of the genes, Fmod, is also a master regulator in the brain that becomes altered by fructose.

The research may lead to new treatments for traumatic brain injury to get the genes to return to their normal state. In addition the researchers potentially could target and modify the master genes so they won’t lead to disease. They may also be able to identify chemical compounds and foods that can fight disease.

Yang’s research is funded by the National Institutes of Health and the UCLA Clinical and Translational Science Institute. Gomez-Pinilla’s research is funded by the National Institutes of Health and the UCLA Brain Injury Research Center.

By Jessica Wolf

For two decades, the field of queer studies has been thriving and evolving within the Humanities Division of the UCLA College. Now Alicia Gaspar de Alba, chair of what is currently known as LGBTQ studies, is ready to take the program to the next level by introducing a Ph.D. It would the first in the nation.

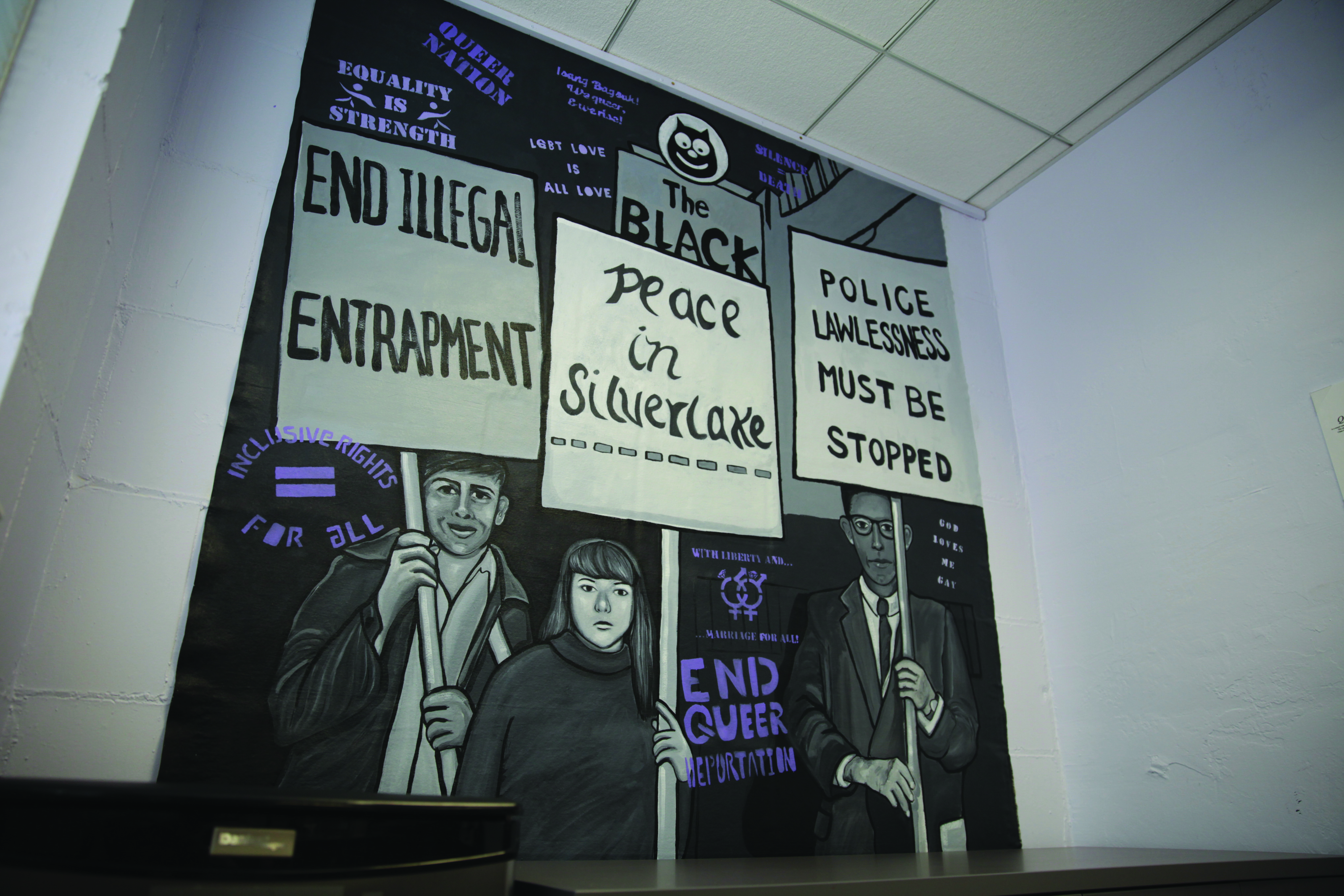

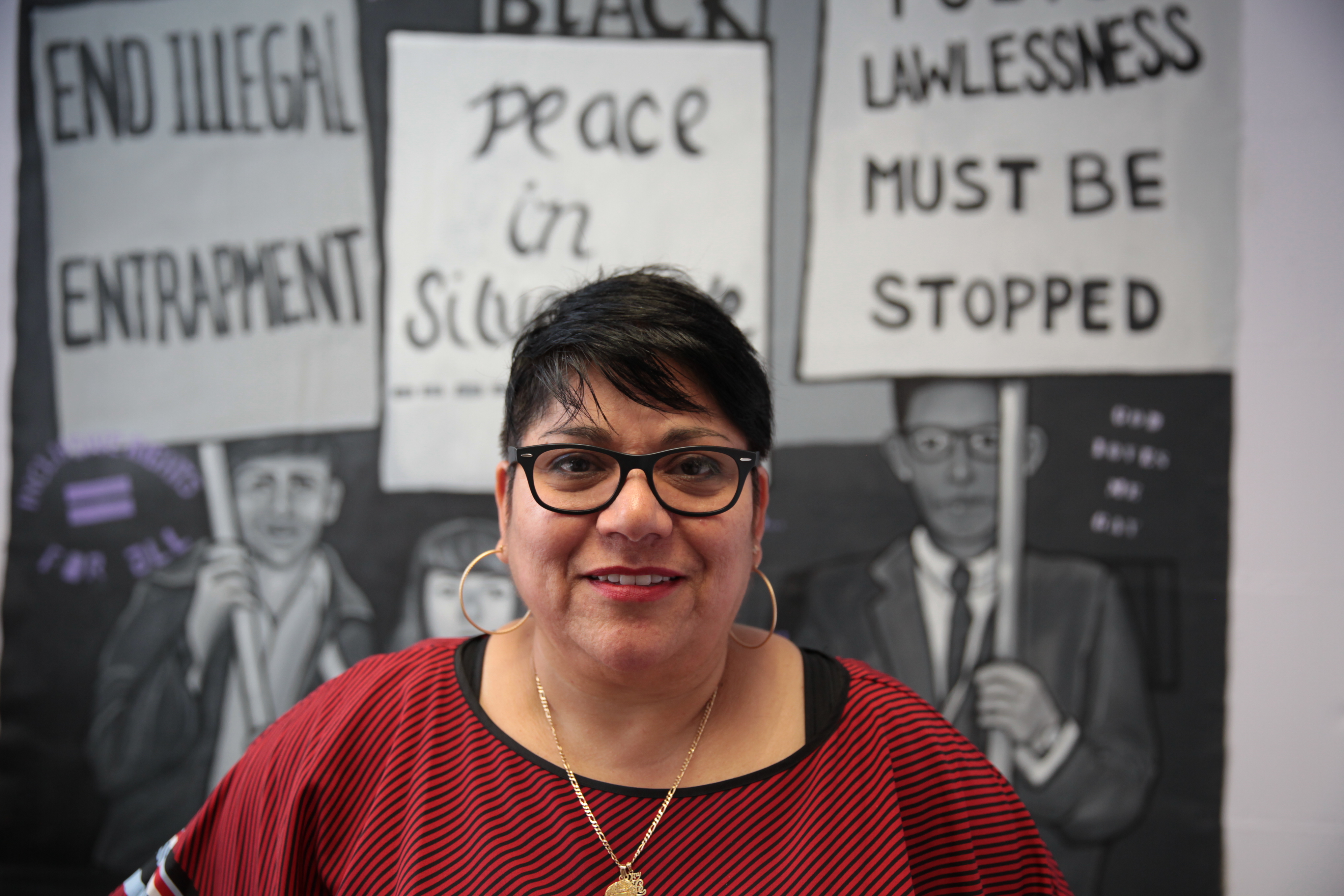

A mural depicting the 1967 LGBTQ rights protests outside the Black Cat Tavern in Silver Lake was installed in the LGBTQ Studies offices in Haines Hall in 2014.

“It’s great that we are still here, that we have survived, but now I’m ready to move forward,” said Gaspar de Alba, a professor of Chicana and Chicano studies. Her Ph.D. proposal is in the works and she is confident it will succeed – particularly because she was the architect of UCLA’s Ph.D. program in Chicana and Chicano studies. A concurrent proposal for changing the program from a freestanding minor to an interdepartmental program with 50 percent full-time faculty is also in progress.

Fall 2017 marks the 20th anniversary of the interdisciplinary program. The program was originally called Lesbian, Gay and Bisexual Studies in 1997, but soon after expanded to add the word Transgender.

Recently, faculty and students decided it was important also to add Queer to that title, catching up to the vernacular of the community. It is now formally known as Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender & Queer Studies.

“It’s the most inclusive word, and absolutely about reclaiming the word ‘queer’ from a pejorative use,” said Gaspar de Alba, who began teaching at UCLA in 1994 and was among the first to participate in the Faculty Advisory Committee that launched the minor.

Pioneering efforts

The formation of UCLA’s LGBTQ studies was championed by former UCLA professor of anthropology Peter Hammond and initially chaired by Jim Schultz, emeritus professor of Germanic languages. At the time it was one of a few but growing number of academic units in the country to examine the history, culture and challenges of queer individuals.

Other comparable programs exist, though at other universities many are housed within a women’s studies or gender studies department.

UCLA’s program has remained autonomous and unique. It was among the first in the country to host an annual graduate student conference, called QGrad. That conference changed in 2005 to a broader Queer Studies Conference. Since becoming chair in 2013, Gaspar de Alba has revived QGrad and added an undergraduate conference called QScholars, both of which are programmed, curated and produced by students under her mentorship. In 2015, the program launched an e-journal called Queer Cats Journal of LGBTQ Studies.

Learning across disciplines

Alicia Gaspar de Alba

More than 120 students have graduated from UCLA with the LGBTQ minor. Exponentially more students have taken cross-listed LGBTQ courses as part of other majors.

Students pursuing the minor choose from relevant courses in a variety of humanities and social sciences departments – English, gender studies, Chicana/Chicano studies, history, sociology – as well as education, law, public policy, musicology and courses from within the Department of World Arts and Cultures and the School of Theater, Film and Television. The program annually hires several UCLA Ph.D. candidates to design new courses, which keeps the curriculum reflective of the issues of the moment.

The minor also requires students to participate in a service-learning course where they intern at local LGBTQ-focused nonprofits.

According to Gaspar de Alba, many former students have gone on to work at those nonprofits or have become journalists, filmmakers and artists. Some go on to pursue graduate degrees, while others aspire to law school and policymaking careers.

Many students join LGBTQ studies out of a desire to know more about the community with which they personally identify. In recent years more students who don’t identify as queer, but want to be allies, also elect to take courses or even commit to the minor, said Tomarian Brown, administrative manager for the program.

Schultz, who returns once a year to teach a section of the introductory course he originally created, said he hopes students take away from queer studies courses a more complex understanding of gender and sexual minorities, and the way those identities intersect with race and social status.

“I think it’s eye-opening,” he said. “Many students will talk about how these courses have opened up their thinking.”

First-year student Meredith Yates specifically chose to attend UCLA because of the LGBTQ studies program. She is the first in her family to leave her home of Virginia to study, and had never traveled outside of the South or East Coast before.

Yates, who volunteers as part of Project One, a team of UCLA students who mentor, befriend and advise queer high schoolers in Los Angeles, hopes to major in communication studies. She plans to return to the South and use her minor in LGBTQ studies to help spread awareness of existing and emerging resources for queer youth who might find themselves feeling isolated. She’s already learning a lot about queer history, she said.

“In the case of the queer rights movement of today, a lot of times we forget that the LGBT rights movement in the U.S., the people who brought it to light, were black and transgender and Latina, people who at the time had been pushed to the very bottom of society,” she said.

Honoring LA’s role in the movement

In the LGBTQ common spaces in Haines Hall there is a remembrance of Los Angeles’ role in fighting for those hard-won rights – and a reminder that the fight is ongoing – by way of a mural depicting the 1967 protests outside the Black Cat Tavern on Sunset Boulevard. It was created in 2014 by UCLA lecturer Alma Lopez and students from her “Queer Art in LA” course.

The mural depicts a scene from 50 years ago this year when members of the queer community and their allies gathered to formally protest the violent New Year’s Eve arrests of patrons of the Black Cat Tavern. These protests predate the well-documented Stonewall riots in Greenwich Village.

UCLA lecturer Alma Lopez led students in creating the mural through her “Queer Art in LA” course.

“Stonewall is seen as the birthplace of the movement,” Gaspar de Alba said. “But we’re here in LA and I wanted to commemorate that the movement for gay rights was actually happening here even earlier.”

Queer studies students are keenly aware

of the challenges this community continues to face, Gaspar de Alba said. Nevertheless, they forge ahead with conviction as they

learn to think and write critically; to inquire, debate and attempt to understand opposing points of view; and to understand themselves.

“These spaces become sacred,” she said, especially for young students who are just coming out. “These classes become places where they can talk about their own lives and issues, but also truly learn to understand others.”

Learn more: http://lgbtqstudies.ucla.edu

“The dream is to have an array of hundreds or thousands of qubits all working together to solve a difficult problem,” said graduate student Joshua Schoenfield. “This work is an important step toward realizing that dream.”

UCLA has offered admission to nearly 16,500 outstanding high school seniors and more than 5,500 transfer students for the 2017–2018 academic year.

![]()

1309 Murphy Hall

Box 951413

Los Angeles, CA 90095-1413

(t) (310) 206-1953

(f) (310) 267-2343