Atomic motion is captured in 4D for the first time

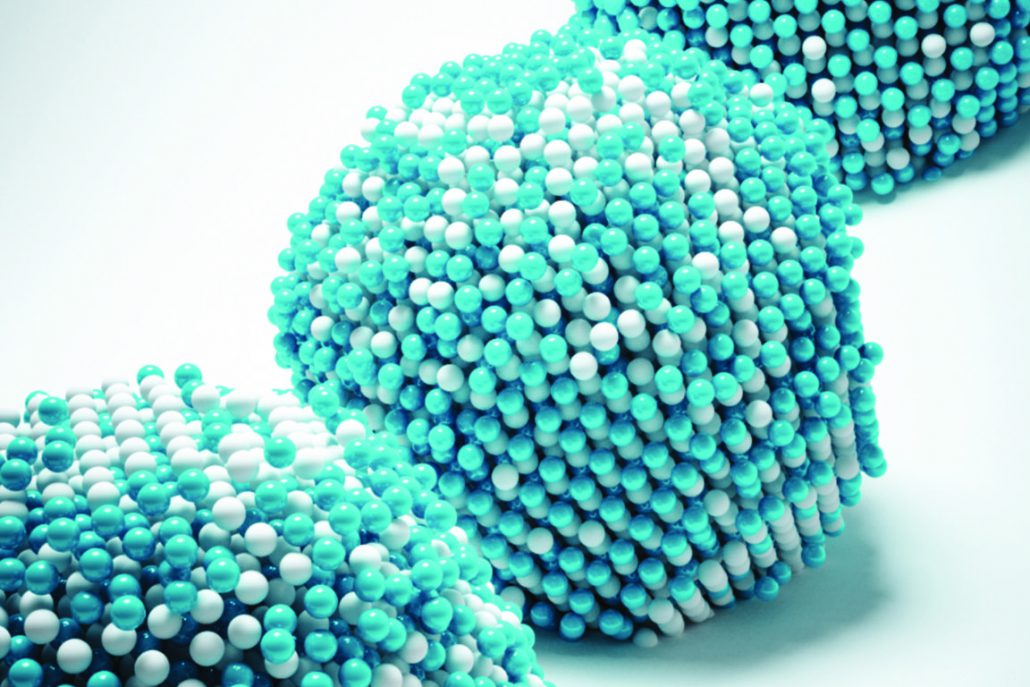

The image shows 4D atomic motion captured in an iron-platinum nanoparticle at three different times.

Credit: Alexander Tokarev

Results of UCLA-led study contradict a long-held classical theory

Everyday transitions from one state of matter to another — such as freezing, melting or evaporation — start with a process called “nucleation,” in which tiny clusters of atoms or molecules (called “nuclei”) begin to coalesce. Nucleation plays a critical role in circumstances as diverse as the formation of clouds and the onset of neurodegenerative disease.

A UCLA-led team has gained a never-before-seen view of nucleation — capturing how the atoms rearrange at 4D atomic resolution (that is, in three dimensions of space and across time). The findings, published in the journal Nature, differ from predictions based on the classical theory of nucleation that has long appeared in textbooks.

“This is truly a groundbreaking experiment — we not only locate and identify individual atoms with high precision, but also monitor their motion in 4D for the first time,” said senior author Jianwei “John” Miao, a UCLA professor of physics and astronomy, who is the deputy director of the STROBE National Science Foundation Science and Technology Center and a member of the California NanoSystems Institute at UCLA.

Research by the team, which includes collaborators from Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, University of Colorado at Boulder, University of Buffalo and the University of Nevada, Reno, builds upon a powerful imaging techniquepreviously developed by Miao’s research group. That method, called “atomic electron tomography,” uses a state-of-the-art electron microscope located at Berkeley Lab’s Molecular Foundry, which images a sample using electrons. The sample is rotated, and in much the same way a CAT scan generates a three-dimensional X-ray of the human body, atomic electron tomography creates stunning 3D images of atoms within a material.

Miao and his colleagues examined an iron-platinum alloy formed into nanoparticles so small that it takes more than 10,000 laid side by side to span the width of a human hair. To investigate nucleation, the scientists heated the nanoparticles to 520 degrees Celsius, or 968 degrees Fahrenheit, and took images after 9 minutes, 16 minutes and 26 minutes. At that temperature, the alloy undergoes a transition between two different solid phases.

Although the alloy looks the same to the naked eye in both phases, closer inspection shows that the 3D atomic arrangements are different from one another. After heating, the structure changes from a jumbled chemical state to a more ordered one, with alternating layers of iron and platinum atoms. The change in the alloy can be compared to solving a Rubik’s Cube — the jumbled phase has all the colors randomly mixed, while the ordered phase has all the colors aligned.

In a painstaking process led by co-first authors and UCLA postdoctoral scholars Jihan Zhou and Yongsoo Yang, the team tracked the same 33 nuclei — some as small as 13 atoms — within one nanoparticle.

“People think it’s difficult to find a needle in a haystack,” Miao said. “How difficult would it be to find the same atom in more than a trillion atoms at three different times?”

The results were surprising, as they contradict the classical theory of nucleation. That theory holds that nuclei are perfectly round. In the study, by contrast, nuclei formed irregular shapes. The theory also suggests that nuclei have a sharp boundary. Instead, the researchers observed that each nucleus contained a core of atoms that had changed to the new, ordered phase, but that the arrangement became more and more jumbled closer to the surface of the nucleus.

Classical nucleation theory also states that once a nucleus reaches a specific size, it only grows larger from there. But the process seems to be far more complicated than that: In addition to growing, nuclei in the study shrunk, divided and merged; some dissolved completely.

“Nucleation is basically an unsolved problem in many fields,” said co-author Peter Ercius, a staff scientist at the Molecular Foundry, a nanoscience facility that offers users leading-edge instrumentation and expertise for collaborative research. “Once you can image something, you can start to think about how to control it.”

The findings offer direct evidence that classical nucleation theory does not accurately describe phenomena at the atomic level. The discoveries about nucleation may influence research in a wide range of areas, including physics, chemistry, materials science, environmental science and neuroscience.

“By capturing atomic motion over time, this study opens new avenues for studying a broad range of material, chemical and biological phenomena,” said National Science Foundation program officer Charles Ying, who oversees funding for the STROBE center. “This transformative result required groundbreaking advances in experimentation, data analysis and modeling, an outcome that demanded the broad expertise of the center’s researchers and their collaborators.”

Other authors were Yao Yang, Dennis Kim, Andrew Yuan and Xuezeng Tian, all of UCLA; Colin Ophus and Andreas Schmid of Berkeley Lab; Fan Sun and Hao Zeng of the University at Buffalo in New York; Michael Nathanson and Hendrik Heinz of the University of Colorado at Boulder; and Qi An of the University of Nevada, Reno.

The research was primarily supported by the STROBE National Science Foundation Science and Technology Center, and also supported by the U.S. Department of Energy.

This story originally appeared in the UCLA Newsroom.