What can Shakespeare, Cervantes, Proust, and even contemporary playwrights and filmmakers contribute to the study of neuroscience?

A lot, says UCLA professor of integrative biology and physiology Scott Chandler.

“When we are talking about the brain, we are talking about our essence,” Chandler said.

For the last four years, Chandler has been teaching and coordinating the pedagogy for the freshman cluster course titled “Mind Over Matter: The History, Science and Philosophy of the Brain.” He designed the course to incorporate medical history and philosophy alongside sections in cognitive psychology and in-depth instruction on neuroscience.

This year “Mind Over Matter” expanded to incorporate literature and film sections that Chandler said have provided valuable context to understand the brain as the home of the human psyche.

This can be a daunting proposition for students and professors alike, he said, but it’s worth tackling.

Looking at the mind through the lens of literature and film

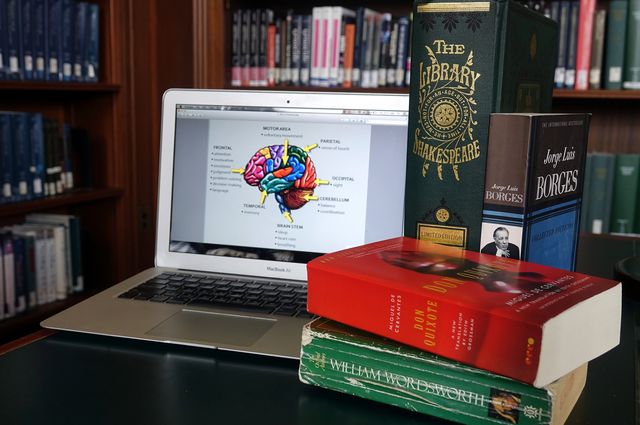

Helping tackle it is professor and chair of comparative literature Efrain Kristal, who inserted a mini-survey of his discipline into the class — which is typically 40 percent science majors. He asked them to dive into representations of mental illness through the lens of Shakespeare’s “King Lear” and Cervantes’ “Don Quixote.”

He followed up scientific and history lectures on the concept of memory with representations of memory in literature through readings from Jorge Luis Borges, Marcel Proust and William Wordsworth.

Wordsworth’s poems provided illustration of memory recall that creates a sense of enrichment or reassurance later in life, he said. Reading Proust’s “In Search of Lost Time” exposed students to the concept of involuntary memory, when present sensations can call up unbidden memories. With Argentine writer Borges, students explored a thought experiment based on the imagined writings of a Shakespearean scholar who inherits Shakespeare’s memories.

They also studied “The Hard Problem” by modern playwright Tom Stoppard, which is set in a neuroscience institute.

“There were characters studying math, psychology and evolutionary biology in the play and they are addressing the practicalities of being in a neuroscience institute, the personal issues involved, the professional dilemmas, and the philosophical dilemmas,” Kristal said. “So through the play we can talk about the implications of what they have been studying scientifically.”

The UCLA College’s division of humanities is developing four curricular tracks — medical, environmental, urban and digital — that teach students to use traditional humanities skills such as close reading and spoken expression to study contemporary issues.

|

As students learned about the history of schizophrenia and post-traumatic stress disorder and their impacts on the physiology of the brain, UCLA comparative literature professor and film expert Romy Sutherland provided an overview of filmmaking techniques that allow viewers to empathize with characters in such films as the award-winning “A Beautiful Mind,” about Nobel Laureate economist and mathematician John Nash and his struggles with paranoid schizophrenia. They also studied “Fearless,” a 1996 film about how two survivors of a plane crash cope with PTSD and “Spider,” by David Cronenberg, in which the lead character suffers from both disorders.

“I approached it as a mini-course on film analysis, and deliberately started with a popular Hollywood movie, then moving to a more middle-ground piece and then moved all the way into the art-house realm with Cronenberg,” Sutherland said.

She said students responded well to examining how filmmakers use the tools of their trade to establish point of view and generate an emotional response toward characters battling diseases related to the brain.

Humanities and sciences can complement one another

There is a growing sense of enthusiasm across campus for increasing the cross-pollination of the humanities with life and health sciences. Deans and educators in the UCLA College and medical schools are exploring the creation of an official course of study dubbed “medical humanities.” This approach would deeply inject courses from multiple humanities disciplines for students in medical degree programs and offer students on a traditional humanities track the chance to broaden their scientific knowledge, which could be applicable in their futures as educators, authors and even artists.

“One of the goals has been to get students, when they leave the course, to see the big picture, and that will help them function better in society,” Chandler said.

The “Mind Over Matter” course is designed to encourage students to think and write critically about the inherent interaction of the neurobiological, philosophical, sociological and psychological factors that control our behavior and experiences as human beings.

“All people need to know about the brain,” Chandler said. “Being able to critically evaluate and understand neuroscientific findings and their potential impact on our society is not only important in medicine, but in non-science professions like law, business and politics, too.”

Students and faculty welcome the challenges

Chandler’s course fulfills general education credits for students in any major. This presents challenges for professors as they offer complicated concepts to a broad student audience in their first year. This course however, is anything but basic; neither the science elements nor the humanities requirements are watered down.

Though the coursework is challenging, student feedback is largely positive. In June 2015, Chandler and his fellow “Mind Over Matter” teachers published findings from surveys of students taken in the second year of the course in the Journal of Undergraduate Neuroscience Education. They found that 77 percent of the non-science majors in “Mind Over Matter” said they would not otherwise have taken a neuroscience course.

“One of the nice things about an interdisciplinary course like this is you can see more clearly that lots of people are asking the same questions, they just come at them from different angles,” said Emma Geller, Ph.D. candidate and teaching fellow for the course. “This is what we’re trying to teach, not that there are always specific answers, but that there is simply evidence and there are ideas.”

Students say UCLA’s cluster course program is invaluable to their research and learning skills. They said they appreciate how the infusion of literature and film also allowed them to examine the brain as a social construct.

“There’s so much we don’t know about the brain,” said James Wilson, who is majoring in statistics and political science. “What I liked about this course was how it fostered both north- and south-campus mentalities on the topic in challenging ways.”

For Youngzie “Zoe” Lee, who is majoring in cognitive science, the course has had a lasting impact. Together with fellow UCLA students and students from other universities who are all interested in continued exploration of consciousness, she has created the Quale, a virtual society where she and other online contributors will continue to share experiences related to the undefinable subjective experience that animates human consciousness.

Creating and teaching a course like “Mind Over Matter” is also challenging for the instructors. Chandler asks that the instructors attend as many of their fellow instructors’ lectures as possible, which Kristal and Sutherland said they found enlightening. They collaborate weekly on class discussions, ask each other questions about how the students are responding and how their areas of expertise can best converge.

“I haven’t worked this hard since I first started teaching,” Kristal said.